Alex Wakelam

[This blogpost examines the petitions submitted by prisoners for debt in early modern England, especially their complaints against prison officials. It uses the case from Ludgate Prison in 1710 to show how the limits of such petitioning and the harsh consequences that could result for those who failed to gather enough support. The post is written by Dr Alex Wakelam (@A_Wakelam), author of Credit and Debt in Eighteenth-Century England: An Economic History of Debtors’ Prisons (Routledge, 2020).]

Every year throughout the early modern period, thousands of English men and women were imprisoned for failing to pay their debts. Most were confined without trial and had little formal recourse to legal aid. They were, however, surprisingly well placed to submit petitions to alleviate or remedy the worst aspects of their experience.

Unlike the felons they were confined alongside, most debtors were drawn from the middling sorts rather than the working poor. Even though they were cash-poor this population of shopkeepers, craftsmen, professionals (regularly including lawyers), and minor gentry were literate, familiar with civic administration, and expected a degree of public sympathy which allowed them to maximise the potential of petitioning.

Courts of Quarter Sessions and civic councils were thus deluged with appeals originating in the debtors’ prisons under their purview. Much of this volume did not, however, require much effort or time to resolve. Thousands of petitions were submitted between 1649 and 1830 to apply for one of the amnesties occasionally passed by Parliament known as the Insolvency Acts. This process was formulaic as courts were only required to collect and catalogue applications; by the 1720s printed petitions were widely available which only required an applicant to fill in their name and address.

Appeals for financial aid might be similarly formulaic. Petitions for financial aid in late seventeenth-century London were almost always seeking a ‘Charitable gift of five pounds for their relief’ implying that this was a routine award which courts merely signed off on.[1] In these instances petitioning was simply a tool of bureaucracy, a method by which debtors claimed aid they were entitled to but for which they had to grovel.

Debtors did raise more specific complaints which touched on all aspects of prison life such as broken pipes, bad ale, leaking windows, their proximity to felons, or, as at the Poultry Compter in 1698, that new toilets (‘the Jakes or House of Office’) be constructed.[2] While these necessitated an active response from the court, they were still probably simple to dispense, merely requiring a release of funds to the prison officers. This did not stop debtors couching such minor grievances in dramatic terms. The debtors of Newgate were far from unusual when in their petition to the Lord Mayor in 1742 for a new pot capable of holding twelve gallons of broth they declared that ‘most of us are So Miserable poor … wee are in A Manner Burried Alive’.[3]

This language of desperation and dependence was expected and required by those in power. However, it leaves the question of how ‘Miserable poor’ the debtors in Newgate actually were. Few petitions left an extensive paper trail and thus exist within something of a vacuum. Debtors were known to exaggerate their woes and such petitions only offer their version of events. Additionally, the complex array of events and negotiations which led to the document which was finally submitted to a court is usually lost. What was left out? How did debtors agree about what to complain? How did their imprisoned status impede their ability to petition? It is even frequently unclear how effective such petitioning was with the exception of those applying for Insolvency Acts which, when checked against prison records, reveal that 85-90% were successful.

When petitions revealed illegal or immoral activity by prison officials, courts could not respond so passively. Grumbling about Keepers was not uncommon. Prison administrators lacked salaries or government funds and ran the gaols for profit which they raised from prisoners themselves through a variety of fees and charging rent on private cells. Keepers frequently stretched without breaching their legal authority to maximise profitability, particularly by minimising their upkeep costs. In a typical 1733 petition against the Keeper of the Westminster Gatehouse prison Francis Geary the debtors claimed he ‘neglect[ed] to furnish the goal as it ought to be and extort[ed] for the lodgings more than is allowable by act of Parliament’.[4] In such instances courts usually simply rapped Keepers upon the knuckles and reminded them of their obligations.

However, when they committed acts of excessive cruelty or illegality such as beating debtors into emptying their pockets or, possibly worse, embezzling civic funds the courts could not sit idly by. Inquiries launched to investigate the complaints and causes of petitions rarely led to systemic change, but they provide unique detail on the organisation, accuracy, and consequences of petitioning from within prisons.

The Case of the Ludgate Prisoners, 1710

On Wednesday the 10th May 1710 three debtors in Ludgate Prison who had been ‘put in the Stocks last Saturday and continued therein till the Sitting of this Committee’ were released by order of the Court of Aldermen of London on condition that they formally apologised to prison administrators. Peter Wingate, William Block, and Thomas Wright had been held by the neck for five days – normal punishments lasting hours – ostensibly for the crime of causing disruption within the gaol and giving ‘opprobrious Language’ to the Keeper and the Steward of Ludgate. However, the prisoners informed the committee their true crime was daring to organise a petition revealing corruption and cruelty within one of the city’s most important debtors’ prisons.[5]

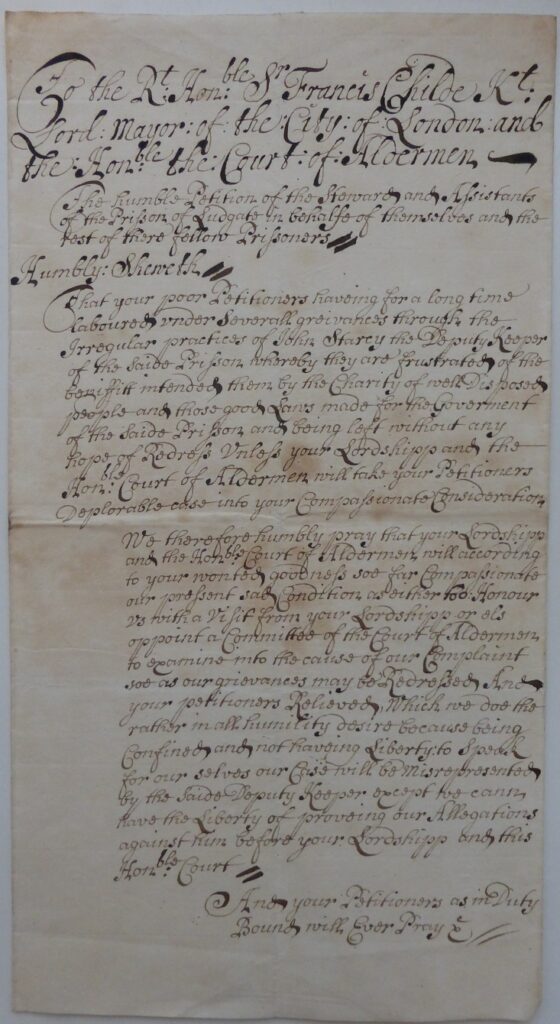

The petition which led the Court of Aldermen to order the ‘Committee for Examining into the Petition of the Prisoners in Ludgate’ does not appear to survive. It was probably similar to one submitted twelve years earlier against the same Keeper, Mr John Stacey, which beseeched then Lord Mayor Sir Francis Child to ‘Honour us with a Visit … or else appoint a Committee … to examine into the cause of our Complaint’, the prisoners ‘being Confined and not having Liberty to Speak for our Selves our Case will be misrepresented by the said … Keeper’.[6] However, the minutes of the committee’s two meetings at Ludgate on the afternoon of the 10th May and on the evening of the 17th do suggest that the petitioners in 1710 were less afraid to ‘Speak for our Selves’ and listed specific grievances in their initial submission.

The inquiry began with Peter Wingate, one of the three petition ringleaders, summarising their complaints with witness statements to support his claims. Many of these were typical criticisms of Keepers particularly that Stacey charged excessive fees (Anne Smith testifying the Keeper had £9 2s 6d from her husband during his ten month imprisonment), that he embezzled the annual bequests from ‘the Lady Rich’s Charity’, and generally treated prisoners roughly and without due respect such as by forcing them to sleep ‘upon the Ground’. More uniquely they claimed he obstructed their ability to work, Thomas Hays complaining that ‘Staicey would not permit him to follow his Trade of a Basketmaker within the Prison till he gave him a Present of 5s Value’, and that the Keeper falsely released debtors but ‘afterwards they were brought back to the Prison again’ in an apparent scheme to extract additional discharge fees. The petition also targeted the activity of the Steward John Hall, claiming that he had embezzled ‘Five Guineas … given by a Gentleman … to be equally distributed amongst the Prisoners’. This was unusual as Hall was not an employee of Ludgate, Stewards being debtors elected from within their number to administer charitable gifts and settle disputes. They were usually older and drawn from the Master’s Side which housed the most prominent debtors who paid a weekly rent for a private room.

Surprised at the Steward’s inclusion, the committee summoned him to explain himself, Stacey following shortly after. The defendants promptly dismissed the petition entirely as a misunderstanding. Hall asserted that while he had indeed been given the five guineas it had been ‘charged to the Account of the House’ as had ‘5s sent by the Lord Mayor at Christmas, And also the £5 mentioned in the Petition [supposedly] to be embezeled’. This he and another witness Mr Sisson testified was common practice: ‘The Steward of the House maintains the Poor who have no Friends at his own Charge … the Steward places [donations] to the Account of the House in Order to Reimburse himself and he had no other way of doing it’. According to Hall, the petitioners were simply ignorant of the process of charity distribution within the prison. Furthermore, their repeated ‘demanding of the Steward a Distribution of the Money’ had led Hall to place ‘Block and others … in the Stocks for 6 hours’ as punishment for demanding selfishly they be given money at the expense of the wider community.

Stacey’s defence similarly rested on prisoner ignorance: ‘As to the Annual Revenue from the White Horse the Petitioners mistake the Fact, For the Lady Rich’s Charity being paid at that House, They take it as they like Sum of The Lady’s Charity issuing from the White Horse by which means that Charity is twice reckoned’. It is certainly probable that Hall and Stacey were lying and trying to dismiss the inquiry as quickly as possible by laughing off the accusations. However, the committee themselves pointed out the ignorance of the petitioners. Regarding their complaint of ‘Distribution of 9 Stone of Beef a Week only, amongst the Prisoners, whereas the allowance is 12 Stone’, the minutes at the end of the first day noted, as the Aldermen well knew, ‘in this their Complaint, the Prisoners are mistaken, for the Allowance of Beef from The Lord Mayor is but 9 Stone per Week’.

Even if the petitioners were mistaken and their case shaky, it is clear both Hall and Stacey suppressed their activity. On the 9th, shortly after the appointment of the committee, a lawyer known as Mr Beasley arrived at Ludgate and discharged Andrew Yateman. A creditor’s lawyer discharging a prisoner after debts had been paid was a common occurrence at the gaol though in these circumstances the petitioners cried foul; Yateman had been a key witness for their case and it appeared his discharge had been enabled by Stacey ‘that he might not be An Evidence’. Attempts to restrict the petition had begun several days earlier when Hall learned the three ringleaders had sent a letter to the Lord Mayor ‘about their Beef which the Steward believed was to Complain against him’ and placed them in the stocks in the middle of the prison yard. While they had previously been pilloried for demanding money improperly this had been only for a few hours and ‘Mr Stacey discharged [them] without any Submission’.

That the three were kept for five days without the Keeper releasing them suggests he supported this attempt to intimidate prisoners into remaining quiet, extending punishment to others who supported the petition. A John Moore claimed to the committee: ‘That for Singing a Petition to the Court of Aldermen complaining of Abuses, and for Carrying the same to the Women also to Sign, [he] was put into the Stocks and sate there 5 Hours’ alongside the ringleaders. This public punishment was a clear warning to others who might entertain thoughts of complaining about their treatment, emphasising the potential obstacles and risks of petitioning within prison.

The consequences of the inquiry for Hall and Stacey were minimal. The committee’s orders (other than that the ringleaders be let go) were limited to ‘That Mr Staicey the … Keeper or John Hall the Steward, or whoever else receives Money upon account of the Prison do enter into a Book to be provided for that purpose the particular Time when and the Name of the Person from whom Received and also for whose Benefit paid’. This process would allow future Stewards to defend themselves against accusations of embezzlement as well as preventing further petitions troubling the Aldermen on this matter. Stacey had also suggested that he be appointed to ‘the Table’ (the prisoners’ administrative council headed by the Steward) and that he be given ‘a Casting Voice in determining of Controversies and punishing Offenders’, a suggestion which clearly did not amuse the committee who noted simply: ‘Rejected’. However, in all other respects the key claims of the petition were dismissed, went unremedied, or were not even properly engaged with by the committee.

The essence of this failure lay not with the inaccuracy of the petition or even Hall and Stacey’s suppression of signatures and witnesses. Instead, it was the failure of Wingate, Block, and Wright to build a consensus within the prison which doomed the petition from its inception. Debtors’ prisons were highly stratified environments; while the majority were drawn from the middling sorts, the difference between those who could pay the 2s 6d per week Master’s Side rent and those on the free Common Side could be as vast as between a labourer and a baronet in the outside world.

If the petition was to succeed it required voices of status or at least the consent of the prison elite as had been done in 1698 when even the Steward signed. Not only did the 1710 petition originate from the Common Side, it singled out a prominent Master’s Side debtor for prosecution. John Moore did at least try and broaden their position by ‘Carrying the same to the Women also to sign’ though the addition of female prisoners whose social status was nebulous at best was unlikely to compensate for the opposition of the upper social strata of debtors.

Unsurprisingly, the Master’s Side closed ranks around Hall and lined up to speak against the petitioners. John Hoseman testified that ‘Wright is a very Contentious Man and breeds Disorders in the Prison, and swore several Oaths when he showed his Dislike to the Division of Beef’, James Bowyer concurring that ‘Wright is a very abusive Man’. Meanwhile George Whittingham testified to Stacey’s generosity: ‘[he] hath been in Prison 9 Weeks and lay in [a] Bed … but has Paid Mr Stacey as yet nothing for Chamber Rent nor has any thing been demanded of him’. Mr Sission claimed Stacey released prisoners ‘actually before he hath received the Money’ for their discharge, extending them credit on their fees. These debtors completely undermined the case of the petitioners and, with their high social standing, no further evidence to the triviality of this appeal was necessary for the Aldermen.

The limits and failures of prisoners’ petitions

While middling sort debtors were in a strong position to launch petitions, the failure of 1710 reveals that within debtors’ prisons their power was not inherent but conditional upon the ability to overcome a series of hurdles. When challenging city officials or men of status within the gaol, these were more complex than being able to grovel sufficiently.

Most importantly, petitioning was dependent upon the consent of the powerful. This applied to even trivial requests, prisoners being forced to flatter those to whom they appealed and phrase petitions for pots and pans in a language of poverty and desperation. Unsurprisingly, their captive status impeded their ability to criticise prison officers. Stacey’s attempted suppression suggests Keepers viewed petitioning as a threat to their authority, fearing court oversight of their administration. Even if a Keeper was unable to halt the appeal, if a petition lacked the support of the prisoner elite – a group with whom the Alderman were likely to have much in common – then organisers risked being viewed as troublemakers and face further punishment. By contrast, a petition from members of the upper echelons of the prison may have been difficult for Keepers to defend against.

Furthermore, as was true in petitioning outside gaols, appellants had to be accurate. It was much safer to ask for smaller bequests, to ask for that which others had already received, or to couch complaints in generalities of suffering and allow the inquiry to identify specific issues. Appeals to rights or crimes in exact terms risked the collapse of a case when officials were able to disprove them, even if evidently behaving improperly in other fashions. From a historical perspective, the 1710 inquiry reminds us to be cautious about petitions as sources on the nature of prison life. Detailed complaints and requests might imply prisoners were aware of their rights and privileges, but that which was confidently claimed in the prison alehouse may not always have reflected reality. This does not mean surviving petitions are not informative of life within early modern debtors’ prisons. The 1710 case was probably somewhat unusual; other petitioners were better organised and usually lacked the poor reputation within the gaol which the three ringleaders seem to have commanded. However, the voices of imprisoned debtors could be as untrustworthy as the Keepers who tried to laugh off any complaint or criticism.

We cannot always take the voices of the oppressed at their word as, even if they had a better grasp over procedure than Wingate, Block, and Wright, petitioners had varied and often hidden motivations. Regardless though of the accuracy of complaints, the reactions of Hall and Stacey to the petition suggest how potent such documents could be in granting power to the oppressed. To some extent, as they hung in the stocks for five days, the ringleaders themselves became victims of the power of petitioning when the traditional elite attempted to stymie its impact.

References

[1] “Petitions of Prisoners, Offices of Newgate and the Compters, and Other Persons relating to Prison Life, Repair of Prisons, Collections, Ill Health, Abuse by Officers, for Discharge, &c”, 1675-1700, Prisons and Compter – General, London Metropolitan Archives (hereafter LMA), CLA/032/01/021.

[2] “The Humble Petition of the poore prisoners in the Poultry Compter”, 1698, LMA, CLA/032/01/021, xxii.

[3] “Petition of Poor Debtors in Newgate Ward”, 1742-3, Debtors Petitions, LMA, CLA/040/08/009, i.

[4] “The Prisoners for Debt in the Gatehouse. WJ/SP/1733/01 (1733)”, in Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions 1620-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/westminster/1733#h2-0001.

[5] “Minutes of the Committee for Examining into the Petition of the Prisoners in Ludgate”, Proceedings of Various Court of Aldermen and Court of Common Council Committees, 1710, Corporation of London – Minutes and Papers, LMA, COL/CC/MIN/01/115, pp.31-33, 35-36.

[6] “The Humble Petition of the Stewards and Assistants of the Prison of Ludgate on Behalfe of themselves and the Rest of Their Fellow Prisoners”, 1698, CLA/032/01/021, lxxvii.