[This post from Dr Andy Burn (@aj_burn) was previously posted on the Durham History Blog. It examines a dispute about a petition to King James I from a group of tenants against their landlord, showing the danger of taking such complaints at face value and the conflict they could create.]

On the morning of 13 October, 1603, Sir Thomas Tresham summoned his tenants to Rothwell parish church, Northamptonshire, like naughty students to the headteacher’s study. He had got wind of a petition they sent to the King in the summer ‘to prevent sr Thomas from renewinge his lease’ of their home village of Orton, on the basis that he had been a cruel landlord. Sir Thomas had been fuming for a while but, ‘respectinge their harvest tyme’, postponed his florid telling-off until after Michaelmas – a not entirely unselfish pause, since they’d been reaping in his rent money during the harvest. And so he dragged the tenants to Church on a Thursday morning to give them an alliterative earful, and to ‘defend his Credytt, … against the infammus imputations which they impudently taxed on him in their petition to the kinge’.[1]

That the tenants had put their names to a petition was not unusual. Then, as now, petitioning was a popular form of politics that attracted wide participation – as the ‘Addressing Authority’ symposium over on the Many-Headed Monster blog laid out. Early modern petitions survive in their tens of thousands, and were used by people of all social ranks to try to improve their lot, or get their voices heard. And, on occasion, to lie through their teeth.

Tresham thought the Orton petition was full of ‘trothelese and infamus Calumniations’ against him, ‘that they, ther wifes, ther Childern and familyes were utterly undone by the extremitye of their fynes, Rentes, paymentes and servis innumerable as by vexationes with processes, and inclosure’. In other words, the tenants had accused him of increasing rents and fines, harassing them for money, and enclosing their shared land – all fairly common stuff in this type of complaint.

When everyone had assembled, ‘Sr Thomas produced the sayde petition and caused yt to be publicklye red’. He then ‘duely proved that their fynes were verye reasonable… [and] that their Rents was as of autentique tyme they had beine’, with apparently little objection from the tenants. None of them admitted being harassed for rent. The enclosure or land that was ‘complaynd of so bytterlye, and with such extremitys of Raylling words’ was no more than four acres. Finally, Sir Thomas ‘proved by testymonie’ that some of the tenants had ‘marked’ the petition even though they didn’t know the contents. By the end of the lecture, ‘all the tenantes of orton … disclaymed from their petition, and in publike presence ther, beseched Sr Thomas Tresame to forgive them’.

This story was recorded in an ‘information’ signed by Justices of the Peace who had been there at the church. Tresham enclosed the document in a letter complaining of being ‘delayed by the peevish and paltry proceedings of my Orton tenants’, but I haven’t (so far) been able to track down the original petition against Tresham, or any further mention of it.[2] In any case, the document paints an unusually vivid picture of the relationship between a landlord and his tenants, and the aftermath of a petition.

We were discussing popular politics on Durham History’s first-year module ‘Early Modern England: a social history’, and petitions inevitably cropped up. I brought along copies of Tresham’s ‘information’ and we considered how far we could read it ‘against the grain’. How do assumptions we make about the motivations of those involved change the way we imagine the scene that unfolded in Rothwell church? We came up with a couple of possible scenarios.

Maybe Sir Thomas was the victim of a mendacious plot to deprive him of his manor. The tenants would have been aware of his uneasy relationship with the Court (an eccentric Catholic, Tresham had spent years in prison and under house arrest[3]), and of the successes and failures of similar action. Petitions were not unfiltered expressions of popular complaints; they were artfully constructed towards a particular goal, sharing rhetorical tropes that were known to be effective. Early modern people (and not just the many lawyers) were familiar with the law, comfortable and confident with how they could use it to their benefit.[4]

On the other hand, maybe Tresham was a consummate bully. What if it had been a genuine petition, filled with real complaints, put down with a display of flamboyant rhetoric and symbolic force? Put yourself in the shoes of the petitioning tenants for a moment. Summoned to the parish church by their priest, under the gaze of their landlord and more than a dozen gentry (not to mention the creepy dogs carved into the pillars at Rothwell), you might be intimidated into silence. JPs were often called on to arbitrate disputes like this, but the signatures suggest that four of the gentlemen present shared the unusual surname ‘Tresham’ – scarcely a disinterested bunch. In the presence of their landlord and his kin, tenants would be used to speaking only when spoken to, and to self-censoring. If not they risked being accused of disrespectful or seditious speech, and finding themselves in the stocks – or relieved of their ears.[5]

Evidently Sir Thomas did ask for the tenants’ input at the Rothwell meeting, but only in answer to a series of leading, almost catechising, questions. Are your rent and fines not fair? Yes they are. Am I not as kind and generous in my terms as any other lord? Yes you are. Were you not wrong to say such mean things about me? Yes we were, and we’re sorry. It took a brave subordinate to speak out alone, and only one tenant seems to have disagreed: ‘one of the tennants [said he] payd twelve pence more then of auntient tyme was payde. To this Sr Thomas replyed that yf yt were so yt was more than he earst knew, but verelie did thinke yt to be untrew’. Case dismissed. Now hold your tongue.

Perhaps the real story was a bit both. If Tresham had been upping rent and building hedges, he wouldn’t have been alone. Likewise, the tenants probably embellished their claims with the help of someone well versed in this kind of law. Perhaps the ringleaders did put pressure on a few of their less willing neighbours to add their mark to the petition. But in the face of a direct confrontation in Rothwell, they (almost) unanimously backed down, and a number disavowed it altogether. Social relations in early modern England were marked by both deference to the established social hierarchy and a defiant and violent streak that frightened elites. But most episodes, like the incident at Rothwell, sit somewhere between these extremes.

References

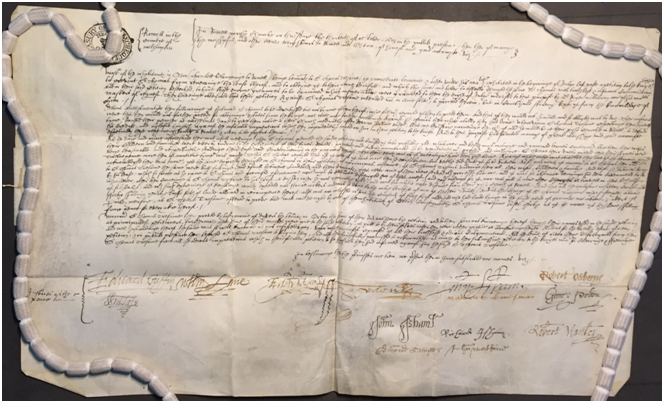

[1] All the quotations are from the pictured document: The National Archives, E 163/16/19.

[2] Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on manuscripts in various collections, Vol 3 (1904), pp. 126-7. Free online: https://archive.org/details/variousmanuscripts03greauoft

[3] See ODNB: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/27712

[4] This was a recurrent theme in papers at the memorial conference for Durham’s Professor Chris Brooks, now published as Law, Lawyers and Litigants in Early Modern England (2019).

[5] Andy Wood, ‘“Poore men woll speke one daye”: plebeian languages of deference and defiance in England, c.1520-1640’, in Tim Harris (ed.), The Politics of the Excluded (London, 2001), pp. 67-9