Emily Rhodes

[This post examines petitions for mercy from women on behalf of themselves or their male relatives who were accused or convicted of serious crimes. It is written by Emily Rhodes (@elrhodes96), a PhD candidate at Christ’s College, Cambridge.]

In 1666, Susan Coe of Rochester, Kent sent a ‘humble Peticion’ to King Charles II.[1] Within, she explained that her husband, the mariner William Coe, ‘being out of Employment and haueing A considerable sume of money due to him from your Majestie’ and ‘destitute of all meanes to subsist by’, stole gunpowder from the Dead Dock at Chatham in order to sell it. The petition further relates how William Coe had been apprehended and ‘confessed the whole matter’ to a Commander Cox, showing that he ‘was heartily penitent’ for the crime. At the bottom of the manuscript and indented, Susan Coe made her request:

‘May it therefore please your Majestie according to your accustomed Clemency & Charitable Disposition in favour of your Petitioner’s husband and in recompence of his former good Services to vouchsafe that his life may be spared for this Offence by your Majestie’s Gratious pardon.’[2]

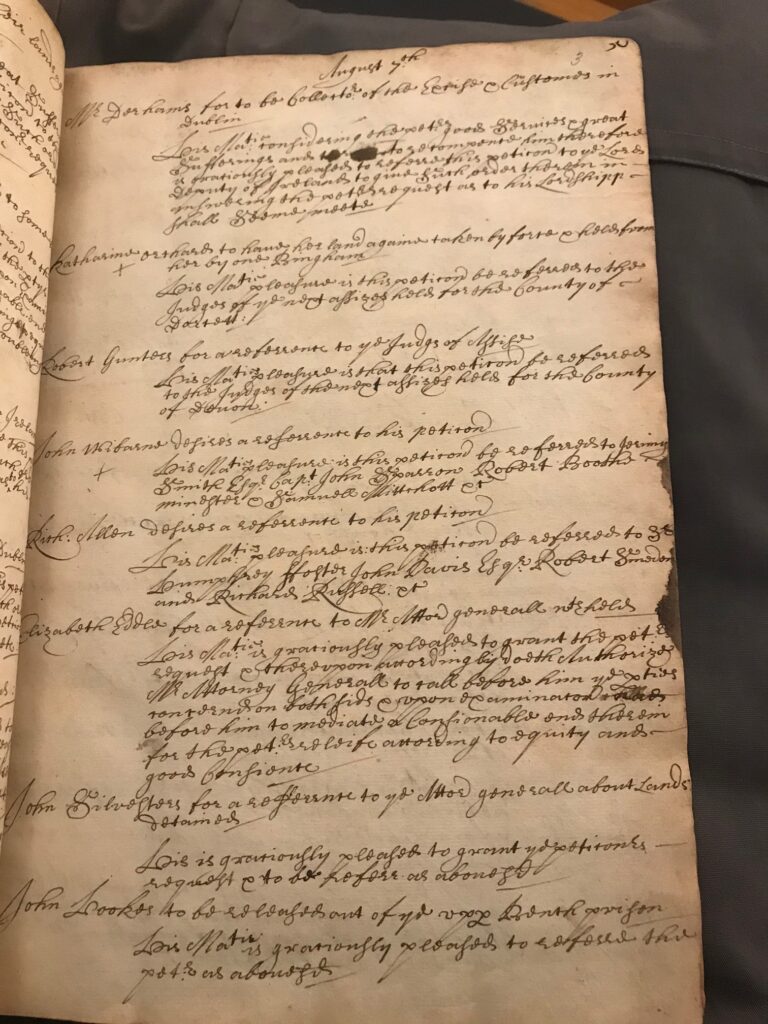

The State Papers in The National Archives at Kew include thousands of petitions submitted to the Crown on behalf of criminals — mostly for pardons, but also to request improved prison accommodation, prison transfers, visitation or fee waivers — which provide historians incredible insight into the lives of common people in late seventeenth century England. Particularly striking is that between 1660 and 1702, at least 160 of these petitions came from women, offering one of the only examples in the early modern period of a direct relationship between even plebeian women and their monarch.[3]

Women would write for themselves, or on behalf of their male relatives: husbands, sons, brothers, fathers, fiancés and sons-in-law. They came from a wide socio-economic background. While some came from the upper echelons of society, others had humble lives — the wives and daughters of labourers and mariners — who frequently stated that without the pardon, they would likely be forced to rely ‘on the parish’. No crime was too big or small to warrant a petition; pleas were submitted for accused and convicted robbers, debtors, coiners, murderers and traitors. Of the female petitions with known outcomes, eighty percent were decided in the supplicant’s favour, demonstrating the political efficacy of early modern women’s voices.

While the number of women’s petitions pales in comparison to the hundreds to thousands of petitions submitted by criminal men, that the female petitions come from so many different backgrounds, regions and circumstances suggests that this practice was widespread. Furthermore, the fact that so many women of so many backgrounds turned to petitioning sheds light on women’s roles outside of the domestic and in the political sphere. Continue reading “Crime and Women’s Petitions to the post-Restoration Stuart Monarchs”