Brodie Waddell

Until relatively recently, the word ‘petition’ had a much wider meaning than it does today. In the twenty-first century, a petition is a request or demand signed by a substantial number of people and addressed to a government authority. Paper petitions are still common among – for example – local activists trying to show support or opposition to changes in their neighbourhoods. However, with the rise of online platforms and social media, we’ve seen the re-emergence of mass petitioning to the national government, signed by huge numbers of people such as the six million who subscribed to one seeking a second referendum on Brexit.

In the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, some petitions looked much like their modern counterparts, but they could also take many other forms. In this post, I’ll attempt to very briefly set out the different sorts of ‘petitions’ that circulated in early modern England and where we can find them in the archives. I’ll devote most of my attention to the three types of petitions that are the focus for our project, but I also discuss others even more briefly. If you want to know more about any of these types, take a look at our annotated bibliography for further reading or our selection of online resources for many original examples.

Petitions to local magistrates

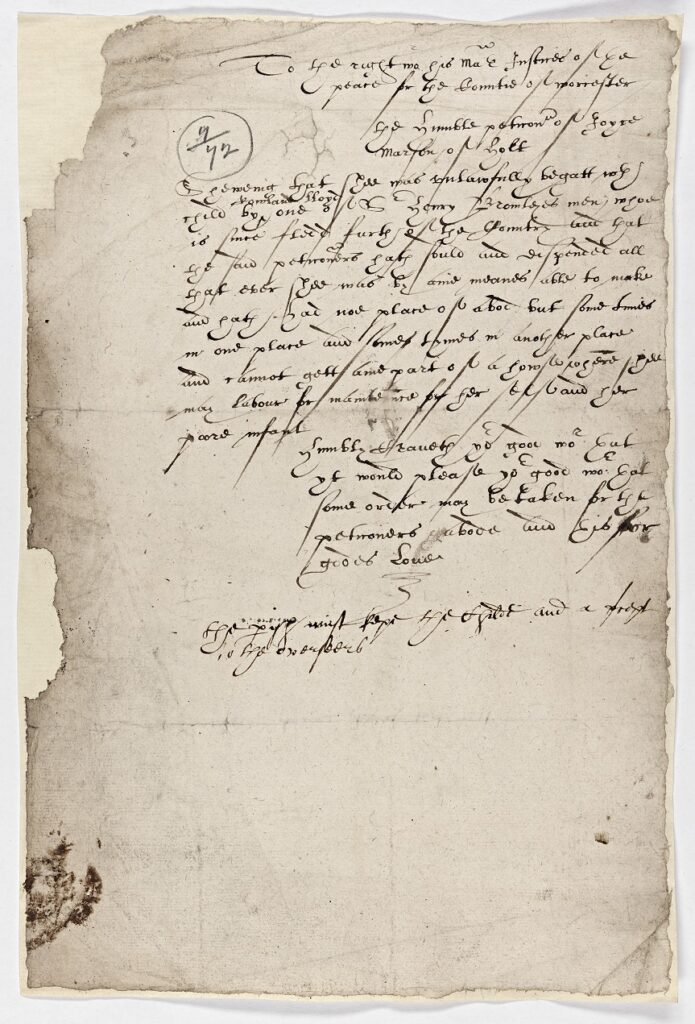

Every city and county authority in England – including mayors, borough councils and county magistrates – received handwritten ‘petitions’ from those who lived within their jurisdictions. For county magistrates, this often took the form of ‘the humble petition’ of a man or woman asking for poor relief, a licence to keep an alehouse or build a cottage, release from parish office, or discharge from a lawsuit. Many also came from veterans or war widows requesting a county pension, especially from the 1640s onwards. Nearly as common as these individual appeals were collective petitions from ‘the inhabitants’ or ‘the parishioners’ of a particular village or neighbourhood asking for adjustments to local taxation, prosecution of disorderly neighbours, expulsion of paupers who legally belonged elsewhere, or adjudication between contending parties.

In both cases, the petitions were often left unsigned – especially those from single individuals. However, in some cases the petitioners might also add their signatures, initials or marks, usually amounting to about six to twelve subscribers, though sometimes twenty, thirty or more names.

The petitions sent to civic officials such as the London Court of Aldermen, the Mayor of Norwich, or the Chester City Assembly usually took a very similar form, though they tended to include somewhat different requests because of their differing jurisdictions. Petitions about apprenticeships – such as release from an abusive master – were more common, as were others related to guilds and the ‘freedom to trade’, though poor relief, local taxation, alehouses and imprisonment were also popular topics.

Although it is difficult to be certain about the process of composition, petitions sent to magistrates were very rarely written by the petitioners themselves, but rather by a professional scribe or literate neighbour – such as a clergyman – who was reasonably familiar with conventions of the genre. Usually, however, the petitioner also had a large role in determining what would be recorded on the page.

These petitions are held in local record offices. For the county magistrates, they survive before c.1700 for about half of England’s forty counties and they are normally preserved in the quarter sessions rolls or papers. They also survive in smaller numbers for some cities that were ‘counties corporate’, which had their own quarter sessions jurisdiction. In many cases, such petitions have not yet been catalogued at the level of individual documents, so the archive catalogue will simply state, for example, ‘Michaelmas Sessions 1645’, and this file will include any number of unlisted petitions. My current estimate is that well over 30,000 of these documents survive from around the 1570s to the 1690s, with the largest number in Lancashire (20,000), Cheshire (5,000), the West Riding of Yorkshire (2,000), Staffordshire, Somerset and Devon (each with around 1,000 or more). Only a small number survive for the sessions of the peace for London and Middlesex before the 1690s, but they amount to almost 10,000 items in the eighteenth century.

For the civic magistrates, they are also common and sometimes survive from much earlier though in smaller numbers. For example, Norwich has about 520 surviving from c.1530 to c.1810, though only 150 definitely date from the seventeenth century. Among larger collections, the City of London Court of Aldermen papers includes perhaps 500 from the 1660s to 1690s and the Chester City Assembly Files holds about 1,400 petitions for the seventeenth century.

Of course, there are many jurisdictions for which few or none survive, but this is due more to the hazards of record-keeping rather than a lack of early modern petitions being sent. Indeed, even where the original petitions have long since disappeared, one can often find evidence of them in the ‘order books’ or ‘minute books’ of local magistrates.

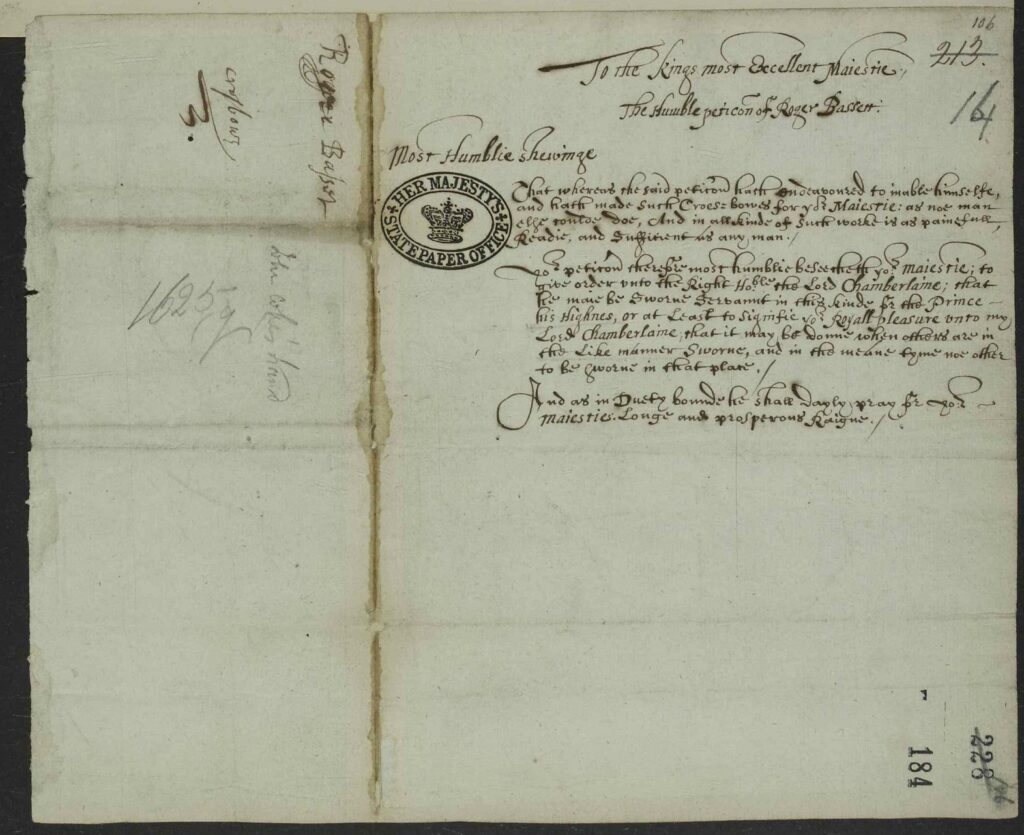

Petitions to the Crown

The King or Queen – or Lord Protector – were popular targets for petitioners through this period and beyond. As heads of state, their jurisdictions were vast and their visibility unmatched. They would have received many unwritten ‘petitions’ from individual suitors in-person, especially semi-formal appeals from courtiers and other well-connected elites. However, they also received an endless stream of paper petitions from across the country and beyond on an infinite variety of matters. As a result, offices such as the Masters of Requests were created that sorted and filtered these incoming petitions.

Further systematic research is needed on this form of petitioning, but it seems that most petitioners were individuals seeking preferment – offices, property, charity – or clemency. There were also many petitions sent to the monarch and privy council from institutions such as those sent by borough councils seeking royal charters or other privileges. Finally, some petitioners focused on issues of ‘church and state’, such as the 16,000 Londoners who signed the ‘monster’ petition to Charles II in 1680 calling for parliament to be reconvened to deal with the Popish Plot. Perhaps the most famous today is the petition from the First Continental Congress in America to the George III in 1774 which complained of the standing army and new taxes. As with petitions to local magistrates, these seem to have rarely been written by the petitioners themselves, but instead the writing was entrusted to an expert scribe who followed well-established rules of composition.

Thousands of petitions to the Crown survive, though many more have been lost. Scholars have found evidence of one royal Master of Requests handling 700 to 800 petitions per year under James I and about 1,000 per year under Charles I, with similar levels received by Charles II in the 1660s. Many of the original petitions are held at The National Archives among the State Papers and have been catalogued in the Calendars of State Papers Domestic, but others are scattered across other series and collections. For example, hundreds more from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century are held at Hatfield House Archives among the Cecil Papers.

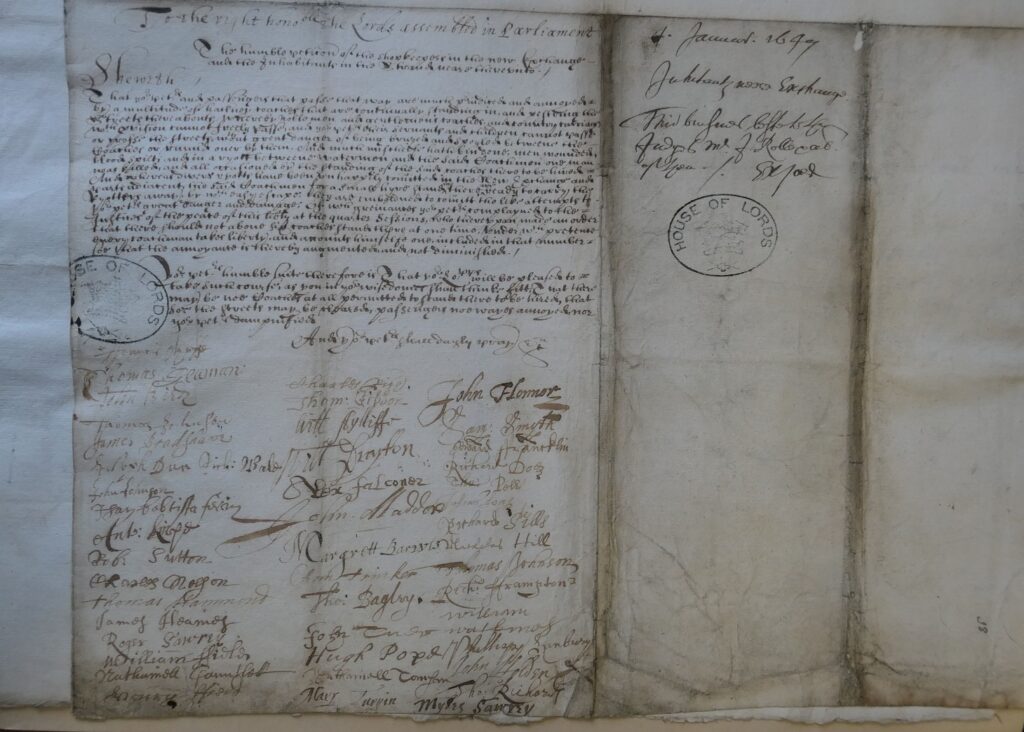

Petitions to Parliament

Both the House of Commons and the House of Lords were frequent targets for petitioning throughout this period. In some cases, they took a very similar form to modern petitions: directed to the national government, asking for a change in public policy, signed by hundreds or thousands of people. This style of parliamentary petition became frequent from the opening of the Long Parliament in 1640, including the famed ‘Root and Branch’ petition calling for the abolition of the bishops, reportedly signed by 15,000 subscribers. However, most petitions to parliament concerned less ‘political’ matters and were often sent by individuals or institutions, such as gentlemen, merchants or whole towns seeking special privileges or adjudication in ongoing litigation.

Unfortunately, virtually none of the original petitions to the House of Commons survive, though there are references to many of them in the Commons Journals and informal parliamentary diaries. Some were printed as stand-alone publications or in newsbooks, allowing us to get a sense of the original text, among them the ‘humble Petition of the Knights, Gentlemen, Ministers, Freeholders, and other Inhabitants of the County of Dorset’ in 1642 asking for the ‘obstructive party’ to be removed from the House of Lords to better pursue the war effort. Around 8,000 manuscript petitions to the House of Lords have survived from the seventeenth century, becoming much more common after the Lords resumed its powers as a court of judicature – and a place to which to appeal on legal matters – in 1621. All of these are held at the Parliamentary Archives and are very well-catalogued.

Other types of petitions

The wide range of petitionary documents that flew around early modern England mean that it would be impossible to provide even a very superficial review of every type, especially as some documents that served overlapping purposes went under different names.

There were, for example, many ‘addresses’ sent to monarchs at this time, sometimes simply congratulating them on victories or marriages but other times including direct requests or even critiques. At the other end of the spectrum, the system of ‘settlement’ created by the Poor Laws led to the emergence of ‘pauper letters’, sent by poor individuals to the overseers of their ‘home’ parishes requesting aid. These were more candid and less formalised than the pauper petitions to county magistrates, though they only seem to survive in substantial numbers from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. Much more constrained were the procedural ‘petitions’ submitted to some courts by litigants to initiate a lawsuit, which followed a narrow legal form. In between these types were the many petitions sent to authorities with other sorts of jurisdiction: to the Vicar General to give a Christian burial to the body of a suicide; to the royal judges on the Assizes circuits from prisoners seeking mercy; to the Navy Board for a particular military office; and so on.

Formal petitions were also sent about matters outside the official jurisdictions of church and state. For example, many absentee landowners – in their role as landlords and ‘lords of the manor’ – received handwritten petitions from their tenants. As with petitions to magistrates, these might be from a single individual or, less often, from a small group. Presumably requests to resident landowners were made in-person orally, but appeals to those residing elsewhere had to be written down. In them, tenants asked for rent abatements, charitable aid, permission to use resources on the property such as timber or favour in other local matters. In many cases, the landlords owned much of the property in a particular village and held additional legal powers as the lord of the manor, so there was sometimes a degree of overlap between petitions to a gentleman as a landowner and a petition to that same gentleman as a magistrate.

Unfortunately, there are no official collections of tenants’ petitions and they appear to survive in much smaller numbers than those sent to local magistrates, but that is at least partly because they usually only survive when preserved among estate papers. Most local record offices hold some, though those may not be catalogued in any detail. Petitions to institutional landlords – such as those sent to Sutton’s Hospital Charterhouse which owned various urban and rural properties – are more likely to have survived. The only substantial published research on these sorts of documents is Rab Houston’s Peasant Petitions and he found about 200 petitions from seventeenth-century Cumberland in the papers of the Percy family and its descendants.

However, to limit the discussion to such formal ‘petitions’ would be misleading. Informal ‘petitionary letters’ were extremely common thanks to the importance of patronage networks in this period, sent by artists, writers, traders and almost anyone seeking the support of someone with more power or prestige. Even prayers to God were often called ‘petitions’, and many of the conventions used in ‘secular’ petitioning can be first found in supplications directed to divine rather than earthly authorities. Indeed, many of the thousands of printed ‘petitions’ in the English Short-Title Catalogue are published prayers rather than political requests.

* * *

So, when reading an early modern document explicitly labelled as a ‘humble petition’, we must remember that it was part of a long, expansive tradition of petitioning that stretched back centuries and encompassed a variety of overlapping genres. It was probably produced through a collaborative process involving the named petitioners, their supporters, occasionally a legal advisor, and a hired scribe. Most importantly, no matter how unique it may appear, it was just one of the hundreds of thousands of ‘petitions’ created in this period and must be understood as part of the wider culture of petitioning in early modern England.