Over 730 petitions addressed to the House of Lords – with a few to the House of Commons – have now been made public on British History Online. Full transcriptions of these manuscripts from the Parliamentary Archives are now freely available to be read online, alongside hundreds of other petitions from local archives and from the national ‘State Papers’.

Parliament was an obvious focal point for people with grievances and demands, as a ‘representative’ institution that played an increasingly active part in encouraging the submission of petitions, and as the highest court in the land. At times, MPs and peers were inundated with supplications, from all corners of the land, and all sorts of people. Due to the devastating Palace of Westminster fire of 1834 – when the papers of the Upper House were deemed more valuable than those of the Lower House – the overwhelming majority of those that survive are contained within the archives of the House of Lords, and the transcriptions in this volume represent a small sample of the texts that have been preserved. Rather than select texts on the basis of important events and famous people, we opted to transcribe as many as possible – usually all – from particular years when Parliament met 1597, 1601, 1606, 1610, 1614, 1621, 1624, 1640, 1648, 1661, 1671, 1679, 1689 and 1696.

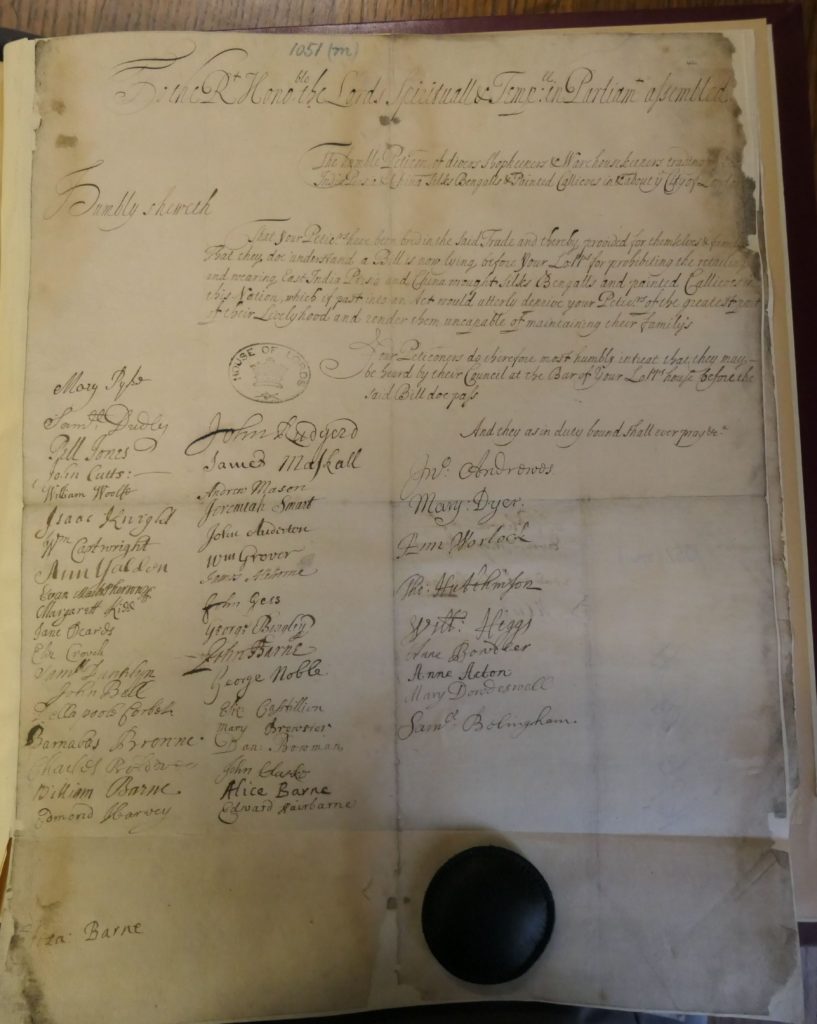

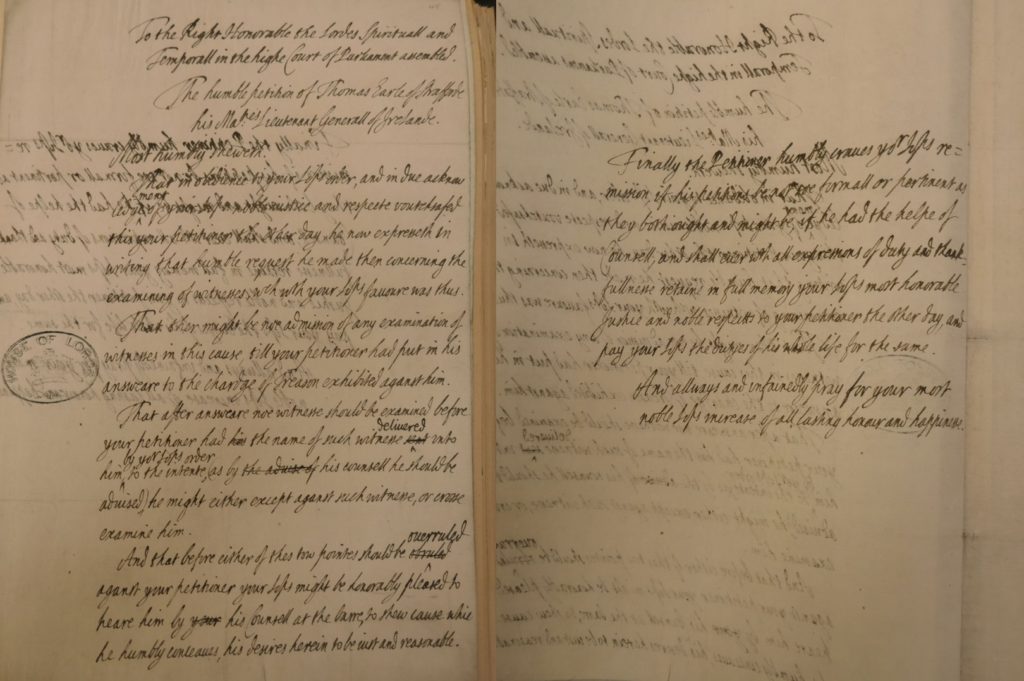

These petitions provide ample testimony about the range of issues that motivated petitioners, about their expectations of Parliament, and about the responses they received. For example, since peers took it upon themselves to address problems with the legal system, they encountered people like Philip Page (1624), who professed to be ‘a poore oppressed prisoner in the comon wardes of the Fleet’. Page narrated a sorry tale of troubles in the Court of Chancery, and of his mistreatment, which was ‘contrary to all equity and conscience’, ‘against common sence’, and indeed ‘fraudulent’. He turned to peers as ‘the principall pillars who support equity and common good’.

![To the right reverend, and right honourable the lords spirituall and temporall in this high and most honourable court of Parliament assembled. The humble peticion of Philip Page [1624]. Image courtesy of the Parliamentary Archives, HL/PO/JO/10/1/23.](https://petitioning.history.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/08/1PagePetition-1024x696.jpg)

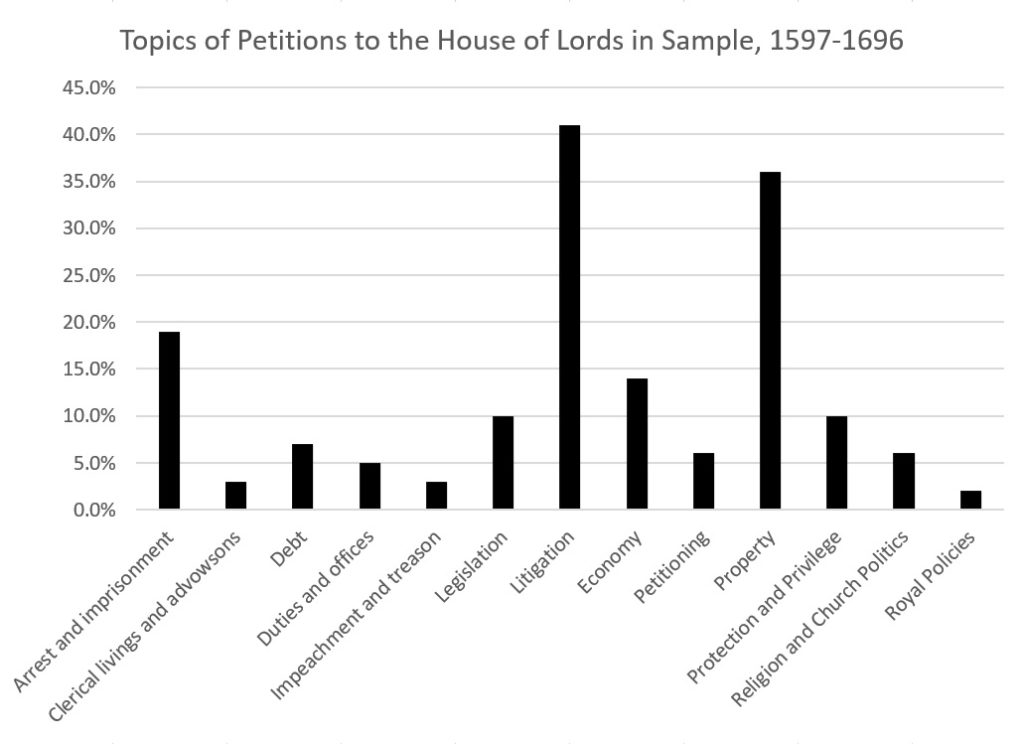

Overall, the topics covered by the petitions in this volume – from rich and poor, and from individuals as well as large groups – ranged across all aspects of contemporary life, from debt and imprisonment to litigation and property, as well as the economy, the church and the state.

Anyone who wants to know more about petitioning in early modern England could start by reading our ‘very short introduction’ and then move on to our annotated bibliography of published scholarship. Each volume also has an editorial introduction offering a brief analysis of petitioners and their business. Further guidance and advice will appear in due course; in the meantime, we hope that these transcriptions prove to be as interesting to you as they have been useful to us:

We would love to hear what you find! Please note that searching is currently by keyword only and spelling was very irregular in this period, so you may need to experiment. We will eventually have a more advanced search facility.

The volume was team effort. It was edited by Jason Peacey and transcribed by Gavin Robinson and Tim Wales. Preparing the texts for online publication on British History Online was completed by Jonathan Blaney and Kunika Kono of IHR Digital.

We are extremely grateful to the Parliamentary Archives who supported the creation of these new transcriptions. Their phenomenal collections provide ample opportunities for further research on petitions, not least in terms of the individuals and communities that appear in our sample. We are also grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for their financial support, without which these volumes would not have been possible.

This volume represents the last of seven sets of transcribed petitions, the others of which include material from the quarter sessions of Cheshire, Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Worcestershire and the City of Westminster, as well as from the State Papers in The National Archives.