This post by Sharon Howard has also been posted on the UK Parliament ‘Petition of the Month’ blog and uses transcriptions from our newly published volume of petitions to the House of Lords.

The 1621 Parliament was summoned reluctantly by the king and achieved little in the way of legislation before being dissolved in early 1622. But it is remembered for other developments that would have long-lasting consequences: the revivals of impeachment, of the Lords’ role as a court of appeal, and of petitioning.

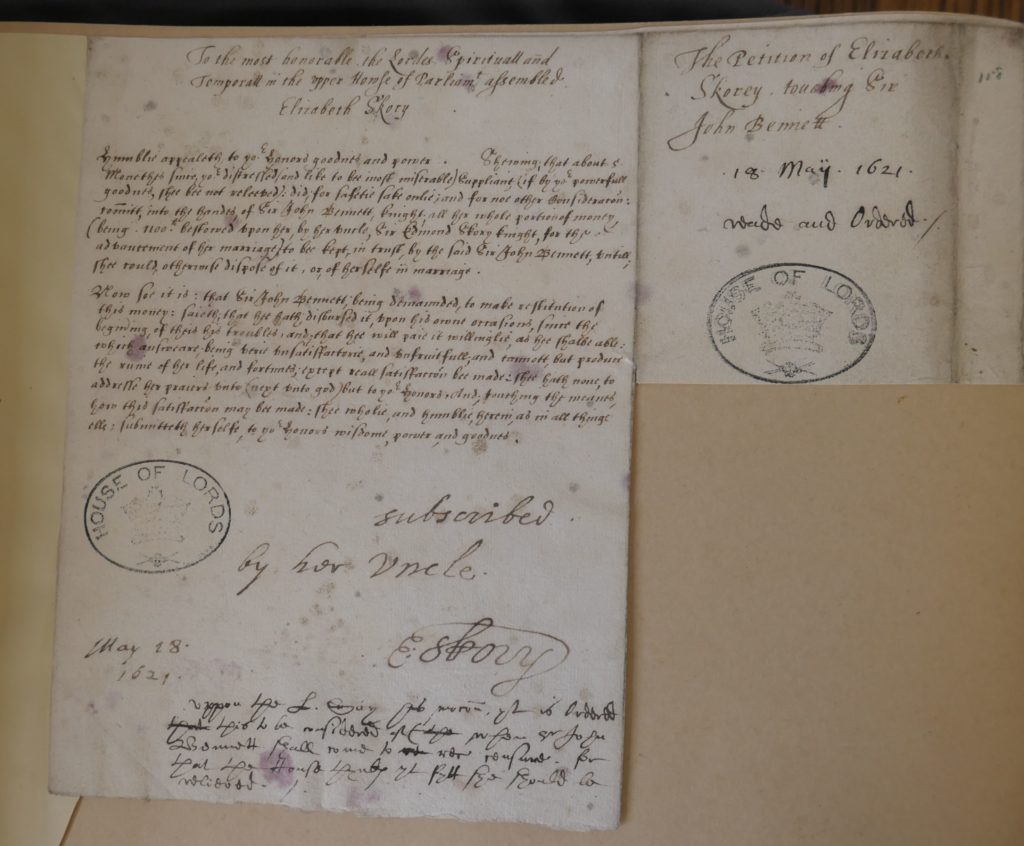

There are just 13 surviving petitions addressed to the House of Lords in the parliamentary archives up to 1620 compared to more than 60 in 1621. Here I look at one of those 1621 petitioners, Elizabeth Skory, who was also among the first women to petition the Lords in the early modern period.

Most famously, the 1621 Parliament brought about the downfall of Sir Francis Bacon, the lord chancellor, for corruption. But Parliament also pursued two other men and their associates during the spring of 1621: Sir Gilles Mompesson and Sir John Bennet. It was the latter who was the subject of Elizabeth Skory’s petition.

At the beginning of 1621, Bennet was a high-flying lawyer and MP who had been appointed a judge of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in 1603. But a string of accusations that he had extracted bribes and excessive fees in his judicial office led to his expulsion from the House of Commons in early May.

The Commons referred the case to the Lords for further investigation, and a stream of witnesses gave evidence against Bennet throughout May. By the time Elizabeth Skory presented her petition on 18 May, it must have been clear that Sir John’s fate was sealed and she was likely to receive a positive response.

According to her petition, some months earlier, she had delivered £1100 to Sir John for safe-keeping, “her whole portion of money… bestowed upon her, by her uncle, Sir Edmond Skory knight, for the advancement of her marriage”. However, when she asked for the money to be returned, he told her that he had spent it in the course of “his troubles” and would pay it later if and when he could. This response “being verie unsatisfactorie, and unfruitfull, and cannot, but produce the ruine of her life, and fortunes”, she prayed for the Lords to come to her aid.

On 30 May, the Lords found Sir John “guilty of much Bribery and Corruption”, producing a long list of the charges found against him, and ordered him to repay Elizabeth. But she petitioned again on 2 June to complain that he was refusing to pay up, and to request a further order to ensure payment; a second order was made on the same day. (The second petition might seem hasty but Elizabeth needed to act quickly, as the king had just announced his intention to adjourn Parliament.)

Like many early modern petitioners, Elizabeth emphasised her helplessness and dependence on the recipient of the petition to save her from total ruin. Her second petition described her as “an Orphan”, who would be “voyde of all relieffe for her whole livelihood and estate” if the Lords did not come to her aid. She was not as desperate and alone in the world as this language suggested. She belonged to a Herefordshire gentry family with a history (if not a notably distinguished one) of public office. Her uncle Sir Edmond was a well-connected author who could spare over a thousand pounds for his youngest niece’s marriage portion, and her sister Anne would later marry Sir Chaloner Chute, who became Speaker of the House of Commons in 1659.

Nonetheless, only Parliament had the power to give Elizabeth such rapid satisfaction, without the expense and delays of a law suit. She was not the only woman to use a petition during the parliamentary assault on corrupt royal officials in 1621. In March, several female goldworkers had petitioned the Lords to complain about their treatment at the hands of one of Sir Gilles Mompesson’s deputies (Hester Favour and Elizabeth Cockren et al). They seized the opportunity created by Parliament’s investigations to try to get justice for their wrongs, and at the same time added their voices to the chorus against abuses of power.

Such petitions blurred the distinction between “private” and “public” petitioning and pointed the way towards more overtly political uses of petitioning Parliament in the 1640s and beyond.