[This post by Philip Carter, Director of Digital and Publishing at the Institute of Historical Research, was original published on the IHR’s ‘On History’ blog on 11 November 2020.]

This autumn the Institute of Historical Research’s British History Online completed a project to digitize and publish over 2,500 petitions from early modern England. The digitization project forms part of The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England, run by historians from Birkbeck and University College London.

The petitions, all now available free on BHO, offer remarkable insight into personal and community relations, preoccupations and language of grievance in early modern England. This makes for an excellent resource for research and teaching. In the final phase of the project, IHR Digital is now building a web interface to work with the BHO data, allowing this rich dataset to be explored in new ways.

Over recent months, editors at British History Online (BHO) have been hearing voices from early modern England. These are not the voices to which historians are most accustomed—those of the elite, literate or powerful whose views come down to us through official records and correspondence. Rather these are the voices of ordinary men and women who came together to raise concerns, submit requests or issue protests, and whose opinions were captured in thousands of signed petitions submitted to local officials, the crown and parliament.

BHO’s encounter with these voices comes from its involvement, as technical partner, in ‘The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England’. This is a two-year digitization and interpretation project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Council and Economic History Society, and led by early modern historians from Birkbeck and University College London: Brodie Waddell, Jason Peacey and Sharon Howard. For the IHR, the project’s been run by Jonathan Blaney, editor of BHO, and our senior developer, Kunika Kono. The original manuscripts were transcribed by Gavin Robinson and Tim Wales.

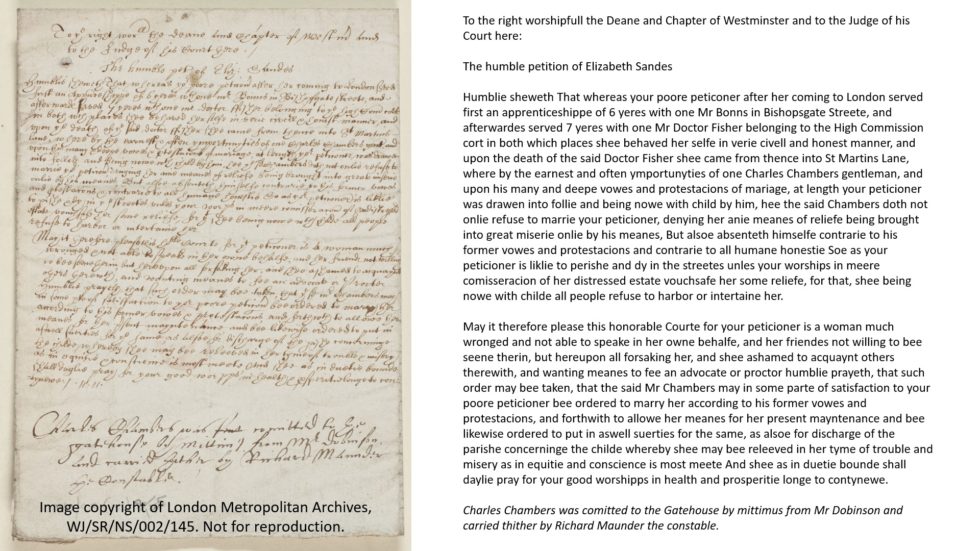

The ‘humble petition’ of Elizabeth Sandes (1620) in which she sought relief from the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey; shown here alongside the transcript published in British History Online. Unless granted, ‘your peticioner is liklie to perishe and dy in the streetes’

The ‘humble petition’ of Elizabeth Sandes (1620) in which she sought relief from the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey; shown here alongside the transcript published in British History Online. Unless granted, ‘your peticioner is liklie to perishe and dy in the streetes’In seventeenth-century England, petitioning was commonplace. It offered one of the few ways to seek redress, reprieve or to express personal and communal interests. Petitions were the means by which the ‘ruled’ spoke directly to those in power. As communications, they took many forms. Some were carefully crafted demands signed by thousands and sent to crown and parliament. Others were hastily written—and deeply personal—expressions of need or anger. Whatever their form, petitions reflect the seldom-heard concerns of supposedly ‘powerless’ people in early modern society.

The IHR’s contribution to the project draws on its extensive experience in the digitization and online publication of medieval and early modern documents—notably British History Online, the Institute’s digital library of primary and secondary resources covering the period c.1200-1800.

Beginning in 2019, the IHR has been responsible for marking up and publishing new transcripts of hand-written petitions held at record offices in Cheshire, Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Westminster and Worcestershire. Additional sets of petitions, now kept by The National Archives and the Parliamentary Archives (and originally submitted to members of the House of Lords), complete the final collection of 2526 documents that now appear on British History Online. Though the majority of petitions were written and sent during the seventeenth century, the earliest record dates from 1573 (this being a complaint against a rowdy neighbour in the Cheshire village of Rostorne) while latest, from 1799, records a request by religious dissenters to establish a new chapel in the parish of Alstonefield, Staffordshire.

The voices that emerge are fascinating. The ‘humble petition’ sent to a local magistrate, for example, could be a personal request for poor relief or a pension on behalf of veteran, support for a widow or unmarried mother, or an apprentice’s plea for release from an abusive master. Others were group petitions written and signed on behalf of a community. Petitions of this kind sought relief from taxation, the removal of paupers to their home parish or the restraint of unruly neighbours who threatened local harmony. Many petitioners were everyday working people—small holders, shopkeepers or traders—who sought to protect their livelihoods when threatened by development or rule changes.

As these examples show, the petitions have much to offer on broader topics of power structures and gender relations, as well as offering hugely valuable insights into the lives of early modern women—as campaigners, advocates, traders and prominent members of business and parish communities. Insights into this and other subject areas feature regularly on The Power of Petitioning’s blog (and Twitter #PowerOfPetitioning) while Introductions to each set of petitions (e.g. Staffordshire) offer expert content and analysis.

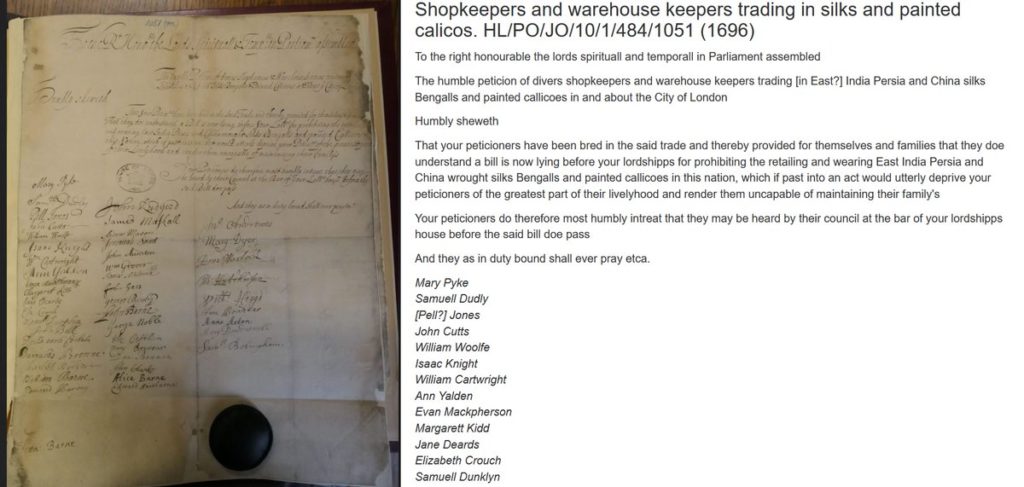

A 1696 petition submitted to the House of Lords on behalf of traders in silks and calicoes, headed by Mary Pyke

A 1696 petition submitted to the House of Lords on behalf of traders in silks and calicoes, headed by Mary PykeThough many of the digitized petitions capture these previously hidden voices, some also feature individuals of national standing. Following his detention by Parliament in late 1640, for example, the lieutenant-general of Ireland, Thomas, earl of Strafford, petitioned the House of Lords for his release—there being (as far as Strafford could discern) no ‘matter in spetiall objected against him’. Consequently ‘Your petitioner humbly beseecheth your lordships he may be bayled’. His plea, however, plea fell on deaf ears and, with the country sliding to civil war, Strafford was executed for high treason in the following year.

Searching the petitions on British History Online reminds us that local grievances also remained pressing even at such times of national crisis. After two decades of revolution, civil war, regicide and republicanism, the villagers of Bramhall, Cheshire, were moved to petition not by Oliver Cromwell or the Protectorate regime, but a smith named Richard Fallowes. His crime was to run an alehouse that harboured drunkards and turned Bramhall into a centre for immorality. The petition drew magistrates’ attention to the ‘the crying noyce of sin’ caused by drunkenness and fornication at the alehouse, and asked that Fallowes ‘may be suppressed from selling of ale and beere for the future’.

As a project recovering the concerns, wishes and disputes of early modern life, ‘Power of Petitioning’ is a striking example of historians’ interest in recovering forgotten or hidden pasts. This is also an important and exciting new departure for British History Online, which has hitherto tended towards historical voices of authority. It’s a new direction that editors are keen to pursue further. If you know of similar content, we’d like to hear from you.

In keeping with its subject matter, ‘The Power of Petitioning’ project is similarly inclusive and civic-minded—bringing together English archives and record offices, the University of the Third Age (U3A) and family historians to work on the transcribed petitions. Freely available as part of British History Online, the 2,526 digitised petitions will remain permanently open to all, and therefore far more accessible than had they simply appeared in a print publication. This also makes for a great resource for online research and teaching across a range of topics: from the dynamics of community or the nature of popular dispute, to the shifting forms and language of early modern grievance and persuasion.

The final set of petitions was published on BHO in autumn 2020. Now, to complete its involvement, the IHR is developing an enhanced web interface to the petitions. This will enable researchers to search and collate the BHO content in additional ways—for example, by date, topic and petitioner profile. The new interface, due for launch in Spring 2021, will offer new ways of questioning the data—allowing further opportunity to eavesdrop on the everyday hopes and grievances of early modern England.

****

Listings and transcriptions of all 2,526 petitions, together with Introductions to each set of petitions, are available from British History Online.