Emily Rhodes

[This post examines petitions for mercy from women on behalf of themselves or their male relatives who were accused or convicted of serious crimes. It is written by Emily Rhodes (@elrhodes96), a PhD candidate at Christ’s College, Cambridge.]

In 1666, Susan Coe of Rochester, Kent sent a ‘humble Peticion’ to King Charles II.[1] Within, she explained that her husband, the mariner William Coe, ‘being out of Employment and haueing A considerable sume of money due to him from your Majestie’ and ‘destitute of all meanes to subsist by’, stole gunpowder from the Dead Dock at Chatham in order to sell it. The petition further relates how William Coe had been apprehended and ‘confessed the whole matter’ to a Commander Cox, showing that he ‘was heartily penitent’ for the crime. At the bottom of the manuscript and indented, Susan Coe made her request:

‘May it therefore please your Majestie according to your accustomed Clemency & Charitable Disposition in favour of your Petitioner’s husband and in recompence of his former good Services to vouchsafe that his life may be spared for this Offence by your Majestie’s Gratious pardon.’[2]

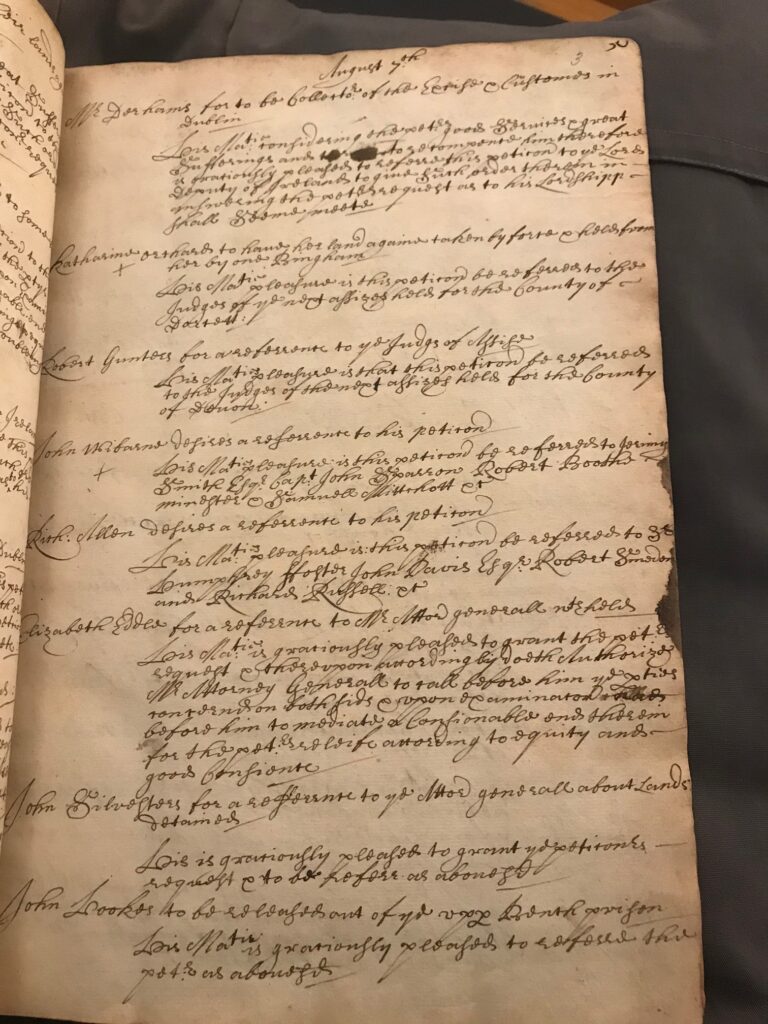

The State Papers in The National Archives at Kew include thousands of petitions submitted to the Crown on behalf of criminals — mostly for pardons, but also to request improved prison accommodation, prison transfers, visitation or fee waivers — which provide historians incredible insight into the lives of common people in late seventeenth century England. Particularly striking is that between 1660 and 1702, at least 160 of these petitions came from women, offering one of the only examples in the early modern period of a direct relationship between even plebeian women and their monarch.[3]

Women would write for themselves, or on behalf of their male relatives: husbands, sons, brothers, fathers, fiancés and sons-in-law. They came from a wide socio-economic background. While some came from the upper echelons of society, others had humble lives — the wives and daughters of labourers and mariners — who frequently stated that without the pardon, they would likely be forced to rely ‘on the parish’. No crime was too big or small to warrant a petition; pleas were submitted for accused and convicted robbers, debtors, coiners, murderers and traitors. Of the female petitions with known outcomes, eighty percent were decided in the supplicant’s favour, demonstrating the political efficacy of early modern women’s voices.

While the number of women’s petitions pales in comparison to the hundreds to thousands of petitions submitted by criminal men, that the female petitions come from so many different backgrounds, regions and circumstances suggests that this practice was widespread. Furthermore, the fact that so many women of so many backgrounds turned to petitioning sheds light on women’s roles outside of the domestic and in the political sphere.

Of course, any conversation about petitions from impoverished people in early modern history must include a discussion of authorship. This is particularly important during a period when it is estimated that only about 20% of women could write.[4] Even if the petitioning woman could write, it was considered improper to write to a monarch in one’s own hand.[5] Therefore, most petitions to the crown were scribed, which raises questions about the extent to which female voices can truly be heard in these petitions. Naturally, drafting petitions was a collaborative affair involving at least the scribe and the supplicant, with the latter dictating the details of the case and request in the manner that they understood it.

Moreover, with these royal petitions, there is another more explicit way to see the woman’s input. Some late-seventeenth century female petitioners sent entreaties to the monarch several times regarding the same case and, in these instances, women evidently did not always use the same scribe, as the hand, spelling and even fold of the paper are visibly different. The content, however, is almost identical, even down to the specific syntax used. This uniformity suggests that these women brought their own ideas to the scribes, rather than the scribes just regurgitating language they considered convincing. But what were the strategies used by women to create a persuasive criminal petition?

Susan Coe pleads for her penitent husband

Alison Thorne has shown that women petitioners frequently exploited the idea of a ‘defenceless woman’, and thus used rhetorical strategies that emphasised ‘their gender identity or familial status’.[6] Returning to Susan Coe’s petition for her husband, we can see her leaning into these gendered tropes. Coe stressed how her husband had only stolen the gunpowder because they were ‘destitute of all meanes to subsist by, himselfe his wife (your Petitioner) and Children ready to starve for want of Bread’. She reiterated this point when saying what he did with the gunpowder, stating that he sold it ‘for the reliefe of his famishing Charge’. In closing, she implored that if he were to be executed, it will be to ‘the utter ruine of your Petitioner and Children’.[7] Coe therefore underlined how important her husband was to the functioning of her family. Without him, the rest of the family would perish. Coe positions her husband as the pivotal member of the family, highlighting her and her children’s weakness and vulnerability in comparison. Whether Coe endorsed these gender relations is of course impossible to know. However, she clearly thought that they would incite Charles’ paternalism and further her cause.

Coe also mentioned her husband’s dire circumstances and positive character traits to illustrate why he was worthy of a pardon from the crown. As previously shown, Coe stated that the mariner had acted ‘through mere want’ rather than due to criminal tendencies. She also focused on his response to being questioned about the crime: ‘he confessed the whole matter and was heartily penitent for it’ — again showing that his actions were not a result of a poor, irredeemable character. Coe further asserted that the wider community held a favourable opinion of her husband. She mentioned that ‘your Petitioners husband was well known to haue been allwayes an able Seamen [sic] in your Majesties Service and well approv’d of therein under his Royall Highnesse the Duke of Yorkes Comand’. Coe presented his Naval connections to highlight that beyond being well-respected in the community, he also was dedicated to the country. Evidentially, she considered this her strongest argument as in her final appeal, she asked for the pardon ‘in recompence of his former good Services’.[8]

Together, these strategies display Coe as a woman trying to present her husband as a good man who only erred to protect his family, who would be destitute without him. This combination of rhetoric was commonly used in petitions to the monarch by women of all backgrounds in the late-seventeenth century. It also clearly was a strategy Charles’ court found convincing, as William Coe was pardoned by the king.[9]

Ursula Tucker complains of injustice

Some women, however, strayed from this tactic. Surprisingly, it was not uncommon for women to critique the judicial system as a means to obtain a pardon. In 1692, Ursula Tucker of Birchington, Kent, petitioned Queen Mary II, begging for a pardon after being convicted at the Kent Assizes of petty treason for murdering her husband, Symon Tucker. In her petition, Tucker held that her husband died after suffering an accidental wound in his thigh and had ‘often declared that he gaue himself the said Wound and that she was innocent thereof’. She also stated that one Chewney had dressed the wound and her husband had told his father — a ‘professed Enemy to the Petitioner’ — not to prosecute her.

Upon her husband’s death, however, Tucker was charged with his murder on the testimony of her father-in-law and Chewney. Tucker proclaimed that during her trial Chewney swore falsely that she had injured her husband, and:

‘she hauing noe Witnesses there and being an ignorant Woman and knew not how to aske pertinent questions that could haue made out her innocency she was convicted of Murther and now lyes under the dreadfull Setence of being burned for the Same.’[10]

Here, Tucker used shortcomings in her trail as rationale for why she should be pardoned. She accused Chewney and her father-in-law of perjury and cited her inability to challenge their testimony on not having or not being allowed — it is unclear — her own witnesses. She also connected her inability to craft an effective defence to her womanhood. Focusing on the testimony in her case rather than her family’s needs provides a contrast to Coe’s petition. However, this technique, while more factual and less emotional than Coe’s, still utilized Tucker’s feminine weakness, expressed here as a lack of legal awareness and credibility due to her gender, as a rhetorical device.

While questioning the decisions of authority figures might seem to undermine the monarch’s power, Tucker’s petition seems rather to reflect loyalty to the crown and a sense of optimism in the queen’s ability to use her judicial role to impart superior wisdom and fairness to pardon Tucker for her unjust conviction. Ursula Tucker was pardoned a few weeks after submitting her petition, thus supporting the idea that this method of argumentation was persuasive to those who read her petition.[11]

Philip Trenchard seeks access to her imprisoned husband

While the above examples show the general form of female petitions used on behalf of criminals, petitions from the wives of men imprisoned for treason followed a different format. This largely was due to the severity of the crime and the fact that many of petitions’ subjects had not been formally convicted or even charged for their accused crime, which changed the goal of the petitioner.

When her Whig husband, Sir John Trenchard, was imprisoned in the Tower of London for six months in 1683 after being implicated in the Rye House Plot to assassinate the King, Charles II, the unusually named Philip [sic] Trenchard petitioned the crown three times.[12] In a contrast to Coe and Tucker’s petitions, Trenchard pleaded ignorance of the particulars of the accusation. Her only specific mention of the crime was a declaration that ‘your Petitioners husband being lately fallen vnder your Majesties displeasure for causes to your poore Petitioner vtterly vnknowne’.[13] Of course, with cases as serious as treason, it was important for a woman to separate herself from her husband and be considered blameless and unaware in the affair to avoid her own arrest.

Trenchard needed to navigate a fine line between supporting her husband, as was expected, and not appearing too sympathetic to his actions. This delicate balance has been noted and studied by other historians such as Sarah-Jayne Ainsworth in her previous blog post.[14] However, Trenchard was unlikely to have been so oblivious to her husband’s actions, as her marriage to John had been a union of two prominent Whig families and she had spent her childhood attending Dissenting meetings.[15]

Perhaps most interesting about Trenchard’s petitions is her requests. Her first petition, received by Charles’ court on 2 July 1683, lamented that she had been ‘deny’d accesse to [her husband] to doe that Duty and Administer those Comeforts which in soe great a Calamnity shee is by the Lawes of God and man Obleidged to performe.’ She ‘therefore humbly casting herselfe at your Majestyes Royall feete implores your Clemency To grant your Petitioner leave to attend and Converse with her husband during his Imprisonment’.[16] This request was granted, but with a caveat: Trenchard could only visit her husband ‘upon condition that she continues in the Tower without leave to come out, unless it be by speciall Warrant.’[17] Perhaps the King and his councillors were worried that husband and wife would use this opportunity to plan more treasonable activities. Evidently this was amenable to Trenchard, as her next petition asked for her release due to her ‘being but 17 yeares of age and by Confinement much indisposed in body’.[18] She must have been successful in this second petition though no warrant for her release exists, as on 5 September 1683, she was once again asking ‘that she may againe have accesse to her said Husband although it may be to the detriment of her owne Health.’[19] What happened after that is unknown, though one can guess that this pattern of petitioning for joining and leaving her husband continued until John Trenchard was finally released from the Tower in December 1683.[20]

With Trenchard’s petitions, we see the opposite of the argumentation presented in Coe’s petition. While Coe stressed how her husband’s execution would affect her and her family, Trenchard focused on how her absence from her husband was detrimental to him and contrary to her duties as wife. She expressed her desire to continue providing for her husband in prison, even if it meant recreating their household there. Her and other women’s treason petitions thus centred on the wife’s role in the marriage, rather than the husband’s.

Furthermore, by continuously referencing how imprisonment impacted her health, Trenchard both drew attention to how awful conditions were in prison —and how much worse they must be for her husband who could not come and go — and also showed the extent of her sacrifice to fulfil her marital duties. Potentially, Trenchard believed that her suffering as a supposedly innocent victim would entice the King to release her husband to spare her.

* * *

Susan Coe, Ursula Tucker and Philip Trenchard’s petitions to the crown in the late seventeenth century show women using the perceptions and stereotypes of female gender roles to achieve their desired outcomes. In these extreme circumstances, they placed their king or queen in the position of caretaker from whom they needed paternal support. These tactics clearly worked — or, at the very least, did not detract from the other facts presented in the petitions — as all these women obtained what they desired. Given how frequently these techniques were used in royal petitions, they also speak to an undocumented female knowledge network that taught women effective strategies for persuasion.

However, the petitioning women and their families were not the only ones profiting from this exchange. Pardons also played an important role in furthering and cementing the power of early modern monarchs, ensuring that the poor felt grateful to and protected by their rulers. As all the late Stuart monarchs had political opponents ready to undermine their authority — Charles II by republicans, James II by Protestants and William III and Mary II by Jacobites — strengthening authority was essential. By keeping the royal pardon as a crucial part of the judicial system and something for which criminals and their families could always hope, late Stuart monarch made themselves essential in this key aspect of early modern rule and the administration of justice.

References

[1] It is important to note that much of this research is based on work done for my MPhil Dissertation in Early Modern History at the University of Cambridge in 2020, ‘Female Petitioning to Monarchs and the Criminal Process in England, 1660-1702’ and also on my undergraduate dissertation at Grinnell College in 2018, ‘To the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty’: Women’s Criminal Petitions to Queen Anne, 1702-1714’. Many thanks to Dr. Clare Jackson and Dr. Catherine Chou for supervising these projects.

[2] The National Archives, Kew (TNA), SP 29/186 f.24a.

[3] This number was found as a result of scouring the State Papers Online archive with the search terms ‘petition’ and ‘crime’, ‘convict’, ‘criminal’, ‘pardon’, ‘reprieve’, ‘gaol’, or ‘prison’. However, I realise that there may be petitions missed.

[4] David Cressy, Literacy and the Social Order: Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 144.

[5] James Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England: Manuscript Letters and the Culture and Practices of Letter Writing, 1512-1635 (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), 87.

[6] Alison Thorne, ‘Women’s Petitionary Letters and Early Seventeenth-Century Treason Trials’, in Women’s Writing 13:1 (2006), 26-27.

[7] TNA, SP 29/186 f.24a.

[8] Ibid.

[10] TNA, SP 44/235 f.279.

[11] TNA, SP 44/341 f.333.

[12] John Trenchard’s wife was seemingly named Philip, rather than Philippa. While a few records name her as Philippa, most – including her gravestone – call her Philip and this is her name in the ODNB. Her petitions are split between the two.

[13] TNA, SP 29/427 f.57.

[14] Sarah-Jayne Ainsworth, ‘The Penruddock Petitions: The Aftermath of a Royalist Revolt, 1655-1660’, The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England, 12 May 2020, [https://petitioning.history.ac.uk/blog/2020/05/the-penruddock-petitions-the-aftermath-of-a-royalist-revolt-1655-1660/, accessed 2 January 2021].

[15] Melinda Zook, Radical Whigs and Conspiratorial Politics in Late Stuart England (University Park: the Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), 33-34.

[16] TNA, SP 29/427 f.57.

[17] TNA, SP 44/54 f.208.

[18] TNA, SP 29/429 f.236.

[19] TNA, SP 29/431 f.145.

[20] Robin Clifton, ‘Trenchard, Sir John (1649-1695)’, ONDB, Oxford University Press, 2008; online edn, [https://doi-org.ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/10.1093/ref:odnb/27705, accessed 29 November 2020].