Laura Flannigan

[This post explores the case of two feuding families who submitted a long series of judicial petitions against each other to a variety of different courts. It is written by Dr Laura Flannigan (@LFlannigan17), who is Lecturer in History at Christ Church College, Oxford.]

Petitioning for justice before the highest authorities in early modern England involved decisions and strategies. By the middle of the sixteenth century, numerous royal courts with overlapping jurisdictions were crammed into the legal marketplace of Westminster: Common Pleas, King’s/Queen’s Bench, and Chancery in Westminster Hall itself, and the courts of Star Chamber, Exchequer, Requests, and Wards in adjoining spaces. Why choose one forum over another? On what grounds did litigants and the lawyers they hired make these choices?

Of course, while royal justice was positioned as a last resort and poorer suitors may have been priced out of its costly proceedings, the more resourceful petitioner sued in as many of these forums as possible. To understand why cross-litigating before the Crown was so popular, and why pluralism developed in this jurisdiction at all, we can examine petitions for cases that appeared repeatedly.

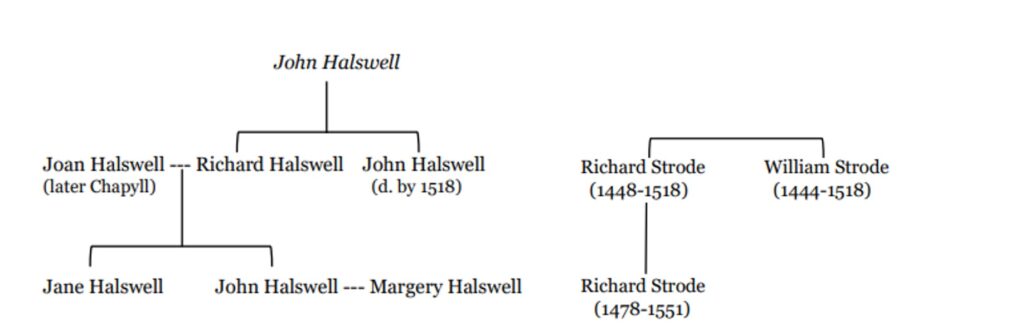

One family feud ran through almost all the central equity courts in the early sixteenth century. Its dramatis personae were the Halswell and Strode families, hailing from Devon. The gentry family of Strode from Plympton St Mary was headed by the elderly William Strode and his brother Richard until both of their deaths in 1518, and thereafter by Richard’s son, also called Richard. Men of considerable standing in the county, they acted as local officials and both Richards sat as MP for Plympton Erle. In managing their estates, they were voracious users of the law. All three men appear regularly in both the central common-law courts and in the equity courts, as petitioners and defendants in suits with their tenants.

Leading the Halswells of Dartmouth were the brothers John and Richard, Richard’s wife Joan, and their children, John and Jane. The Halswells left little trace in the historical record, so were presumably poorer than the Strodes. John Halswell senior had sold his lands to make up for various debts owed and was described at one point as a ‘common land seller’. But the younger John Halswell was said to be a ‘yeoman’ and was able to hire a serjeant at law as his legal counsel.

The dispute between them produced at least seventeen separate suits, with twelve surviving petitions in the central archives.[1] Taken together, they illustrate the perceived differences in the character of each royal court and the strategies adopted when petitioning to them.

As each petition sets out, the root of the argument between these families was a complex battle over the right to lands and tenements laying between their respective hometowns in the parishes of Ermington, Yealmpton and Brixton (one parcel of which was actually called ‘Halswell’). The Halswells claimed these properties by descent from a long line of ancestors. Yet apparently, in lieu of a debt owed, John senior had sold them to William Strode for just £22 – far less than their true value. Strode neglected to pay the Halswells or return the lands after his term was finished. He also pushed out another man called William Gyll (to whom John Halswell senior granted part of the lands in c.1500) by threatening to ‘undo hym by sute’, and had taken the property and its profits ever since.[2] Following William Strode’s death in 1518, these assets passed into the hands of his nephew, Richard, who continued to collect rent and had allegedly wasted the houses and pillaged the grounds to the tune of hundreds of pounds worth of damage. From this starting point the feud escalated to the royal courts of justice, where it remained for decades.

The case was pursued first by the Halswells in several suits before the Court of Requests, a judicial arm of the main royal council that heard the cases of ‘poor’ suitors. The first petition, from the mid-1510s, does not survive – the case appears to have been dismissed at the behest of the Strodes – but the second, from the early 1520s, does. Unusually, given that this court technically resided outside the statutes of English common law, Halswell’s petition framed Richard Strode’s damage to the lands as being ‘contrarye to the form of the statute therof late made concerning the dekaye of houses & husbondrye’, referring to an act passed at the parliament of 1514. Halswell thereby appealed to the king as ultimate lawmaker. Otherwise, the petition’s rhetoric was standard for the ‘poor man’s court’ of Requests. Richard Strode was described as ‘a man of gret londes substans & goodes and of alyans yn the said countye and your said suppliant but a very pore man’. In later petitions to Requests, it was also alleged that Strode had bribed local justices ‘by greet gyftes and rewardes’.[3] This emphasis on disparity between the parties and a barrier to remedy elsewhere justified suit to Henry VIII under exceptional circumstances.

Around the same time, Richard Strode counter-sued with three separate petitions to the court of Chancery, addressed to the Lord Chancellor, Thomas Wolsey. Compared to the Requests petitions, these bills are much shorter, less emotive, and more formulaic. The first rehearsed only that the evidences and charters for the lands that Strode claimed had come into the possession of John Halswell senior. Strode told how he had asked Halswell repeatedly for these documents but ‘hee utterly refuseth … contrary to all faith and good conscience’. This denial, Strode argued, precluded him from suing for the lands in the common law courts, where these evidences would be required. The rest of the details were left out. The second and third of Richard’s petitions made near-identical allegations against Joan Halswell – the widow of the then-deceased John – and John Gyll, the brother and executor of the aforementioned William Gyll.[4] Strode’s approach to the matter was more straightforwardly legal and technical, treating the relatively novel jurisdiction of Chancery as a means to the (perhaps more lawful) end of a ruling under English common law.

With no resolution forthcoming, the following decades saw the same arguments put to a range of different jurisdictions. At some point, Joan and John Halswell sued Strode themselves through Chancery, resulting in an inquest overseen by John Gilbert, a former Requests judge in Totnes. In c.1539, Halswell petitioned several times to the Council in the West, a short-lived offshoot of the royal council, where he was finally awarded title to the disputed properties after Strode failed to produce any evidence for his claims. Strode refused to obey this order, and so Halswell petitioned Star Chamber in 1541. By this point, the matter had become so complicated that it was committed by the Lord Chancellor to the Chief Justice of Common Pleas and then eventually dismissed to the common law. In the meantime, because Henry VIII dissolved the Council in the West, Strode ‘entred in to the premysses & therof expelled youre said poure subiecte’, Halswell told Requests in a new suit undertaken in Requests in 1543.[5]

Strode then took the offensive. In the early 1540s, he petitioned to Star Chamber, telling how on one November day John Halswell and his accomplices had driven some of Strode’s cattle to Stokenham, in the Halswells’ part of the county, declaring that ‘we shall borrow a pece of the law’ and thereby receive recompense from Strode. At Stokenham a crowd gathered, shouting ‘kylle the horesyn thevys & a downe with them’ at Strode and his entourage. Among the rioters taking aim at Strode with arrows and weapons was John Halswell himself, armed with a sword and a long staff, and his wife Margery and mother Joan, throwing stones. Strode used his petition to beg the Chancellor for ‘hasty reformacion & dew correction of these evyll & misdemeaned persons’, setting an example for others in the area who might be tempted to rebel.[6] On this occasion, Strode omitted details of the legal battle that had been waged between these parties over the last three decades, concentrating instead on this single episode of alleged violence.

We don’t need to unpick all the technical details of this case or be able to tell every Richard or John apart to see that these litigants had choices about where to send their complaints. Some were even confident and well-advised enough to take advantage of the capacity for re-litigation in the legal system.

But it’s also clear from the Halswell v Strode saga that resourceful litigants and legal counsel knew how to appeal to the required petitionary frameworks of each court: emphasising disparity and disadvantage in Requests, riot and royal peace in Star Chamber, and technical legal matters in Chancery and the common-law courts. The variability of narratives offered in this single dispute reminds us that petitioning was about providing a story for the official record as well as for remedy. In 1640, the Long Parliament’s act to dissolve the larger part of the royal jurisdiction would point to ‘much incertainty… concerning Mens Rights and Estates’ abounding within these courts.[7] The power of petitioning may not have saved such popular forums in the end, but it likely created the diversity of jurisdictions in the first place.

Appendix

List of (known) cases between the Halswell and Strode families in the central equity courts:

1510s – John Halswell (senior) v William Strode – Court of Star Chamber (STAC2/22/373)

c.1515-1518 – Richard Strode v John Halswell – Court of Chancery (C1/443/19)

c.1518-1529 – Richard Strode v Joan Halswell – Court of Chancery (C1/570/1)

c.1518-1529 – Richard Strode v John Gyll – Court of Chancery (C1/570/2)

c.1519-22 – Richard Halswell v Richard Strode – Court of Requests (no surviving petition)

c.1523 – Richard Halswell v Richard Strode – Court of Requests (REQ2/3/134)

1520s – Assize of novel disseisin – John and Jane Halswell v Richard Strode -> ‘treaty’ made

1520s – Joan Halswell v Richard Strode – Court of Chancery (C1/600/23) -> commission in Totnes

c.1539 – John Halswell younger v Richard Strode – x 3 – Council in the West (no surviving petitions) -> order in Halswell’s favour

1538-1544 – Richard Strode v John Halswell – Court of Chancery (C1/1063/78-79)

1541 – John Halswell v Richard Strode – Court of Star Chamber (either STAC2/18/238 or STAC2/30/24) -> committed to Lord Baldwin, Chief Justice of Common Pleas in 1542 -> examined September 1542 à remitted by Lord Chancellor back to the common law in c.1543

c.1541/42 – Richard Strode v John Halswell and others – Court of Star Chamber (STAC2/20/311)

c.early 1540s – Richard Strode v Walter Chubb and others – common-law session in Ermington

1543 – John Halswell v Richard Strode – Court of Requests (REQ2/4/394) -> heard until 1545

c.1544-45 – John Halswell v Richard Strode – Court of Star Chamber (either STAC2/18/238 or STAC2/30/24) -> decree in Halswell’s favour in May 1545

c.1546 – Richard Strode v John Halswell – Court of Star Chamber (STAC2/28/1)

References

[1] These are: TNA REQ2/3/134, 2/4/394; C1/443/19, C1/570/1, C1/570/2, C1/600/23, C1/1063/78-79; STAC2/18/238, STAC2/20/311, STAC2/22/373, STAC2/28/1, STAC2/30/24. See Appendix for a timeline.

[2] TNA C146/1790

[3] TNA REQ2/4/394

[4] TNA C1/443/19, C1/570/1

[5] TNA REQ2/4/394

[6] TNA STAC2/20/311

[7] Habeas Corpus Act, 16 Car 1 c. 10