We recently published The Power of Petitioning in Early Modern Britain, an open access collection of essays available to read for free from UCL Press. One of the editors and contributors is Jason Peacey, Professor of Early Modern British History at University College London. We asked him about his chapter on ‘‘The universal cry of the kingdom’: petitions, privileges and the place of Parliament in early modern England’ and its place in his wider research.

* * *

How did you get interested in early modern petitioning?

My interest in petitions relates to a concern that drives much of my research: the relationship between structures of power and ‘ordinary’ members of the political nation. I am interested, in other words, in the interactions between the state and the citizen (or subject), and in how power dynamics changed across the early modern period. This has involved research into the impact of the print revolution, in terms of how novel forms of media provided access to ideas and information, and facilitated political participation, not least in relation to Parliament, the power and importance of which has been central to historiographical debates for a long time. Petitions, like elections, provide a valuable means of analysing perceptions of, as well as interactions with, Parliament, and a way of assessing how peers and MPs reacted to being more closely observed, and to the ‘clamour’ of petitioners, whether individually or collectively.

Indeed, for a period when the franchise remained somewhat restricted (if not perhaps as restricted as some would assume), petitioning can be said to have been crucial to how contemporaries understood the role of Parliament as a representative institution, in terms of how far it could and should respond to pressure from ‘without doors’, and perhaps even to public opinion. In all sorts of ways, people in the early modern period grappled with thorny political issues, and petitions provide a wonderful tool for any historian who is interested in analysing the messy struggles to establish appropriate practices and protocols regarding the conduct of public life.

What is the most interesting petition or petitioner that you came across while researching this chapter?

My chapter is based upon a wealth of apparently obscure petitioners, who collectively reveal what seems to me to be an important story. Necessarily, few of these characters proved easy to contextualise, in terms of how they ended up as petitioners, although it is tempting to think that each and every one of them had an amazing story which cries out to be recovered. One of them, however, was already known to me from my previous research. Benjamin Crokey was a fairly obscure Bristol merchant, whose life and tortuous legal battles can be reconstructed from a remarkable – if tangled – body of surviving documentation.

He was one of the protagonists in a long-running dispute (a kind of early modern Jarndyce vs Jarndyce) over a small estate in rural Gloucestershire, which appears to be somewhat mysterious, but which can be shown to have been driven by serious issues, not just in terms of the conduct of litigation, but also in terms of political and religious conflict. Crokey is a bit-part player in my chapter, but his back-story helps to make sense of the wider landscape that is explored, in terms of the grievances that drove people to petition Parliament, their hopes and expectations, and the ways in which they were treated. Ultimately, he makes it possible to understand the willingness of MPs and peers to help humble supplicants, even if this meant acting in ways that proved to be controversial.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading your chapter?

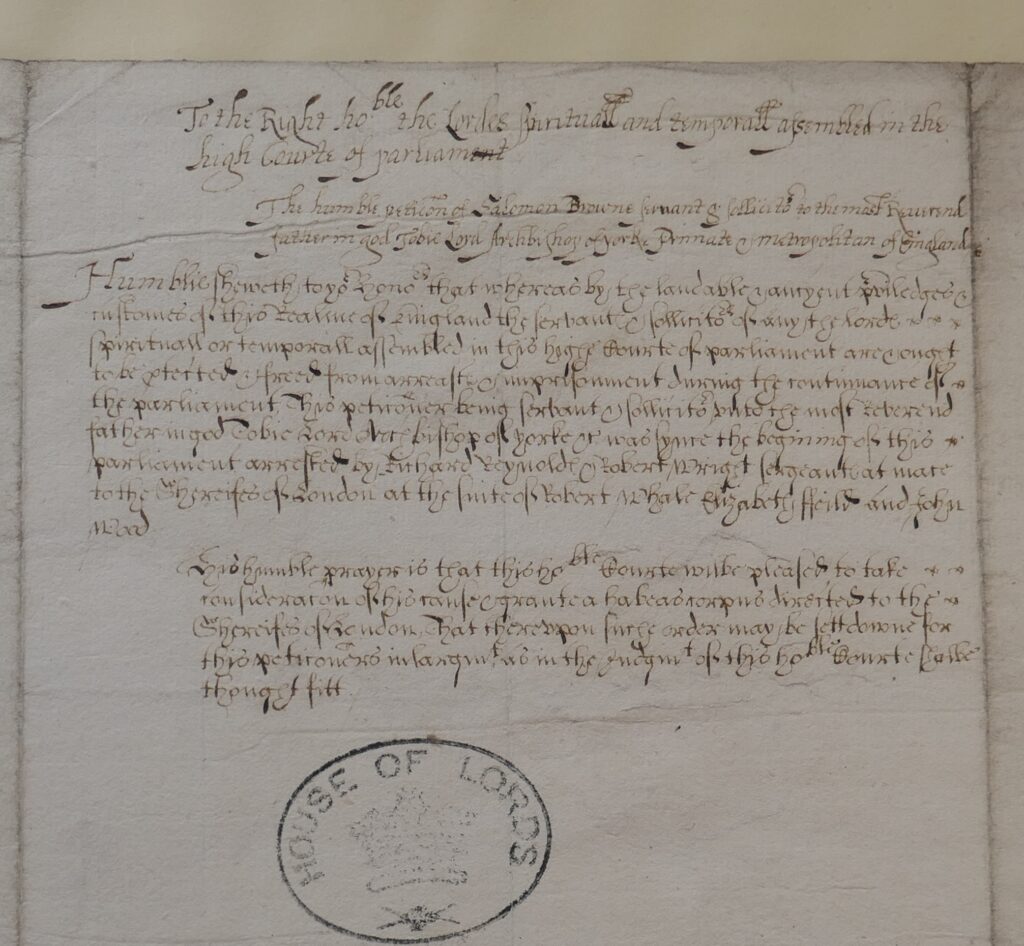

My hope is that readers will gain a new perspective on the significance of Parliament within the early modern political landscape, and indeed the political imaginary. Too often, it seems to me, the place and power of Parliament, as well as its fluctuating fortunes, have been analysed in relation to constitutional conflict, and in terms of contestation with the crown. Historians thus debate the ‘rise’ of Parliament in ways which assess the severity of tensions between different ‘estates’, from the accession of James I (and earlier) to the Glorious Revolution, by way of the civil war and revolution. Central to this story and these debates are issues relating to the powers claimed and exercised by Parliament, including those liberties and privileges that lie at the heart of my chapter.

My aim is to recontextualise one such privilege – the ability of peers and MPs to ‘protect’ their servants from arrest – and my hope is that readers will be persuaded about the need to think not just about members’ willingness to flex their institutional muscles in order to challenge successive monarchs, but also about their responsiveness to petitioners, and indeed about the extent to which petitioning inspired policy changes and institutional reform. Ultimately, my hope is that the chapter will provoke further research on how petitioners were treated, on how politicians thought about their responsibilities towards supplicants, and on the extent to which the development of Parliament as an institution reflected its growing importance as a focal point for the public, and for anyone with a grievance that needed to be addressed.

How does your work on this chapter fit into your current and future research?

One of the most fascinating things to emerge from the research for this chapter has been the potential for studying the responses that petitions elicited. This is a neglected area of research, but scrappy annotations as well as some surviving registers provide vital evidence about whether individual petitions were accepted or rejected, about the speed with which they were handled, and about the care with which they were sometimes considered. In future, I plan to do more work on such evidence, not least in order to complement a chapter which focuses on the responsiveness of Parliament with another essay which assesses when and why petitioners were turned away. Both topics are arguably vital for understanding how Parliament was viewed, from within and from without, and how perceptions changed over time. Indeed, setting such evidence about reactions to parliamentary petitions alongside similar registers that record royal responses to supplications will make it possible to assess the relative value to contemporaries of Crown and Parliament.

Ultimately, my aim is to feed further research on petitions and petitioners into a much broader study of early modern citizenship, defined as activities that brought ordinary people into direct contact with national institutions, and involved some kind of political participation. As a topic, citizenship is most often studied in relation to ‘rights’, which might lead to the conclusion that it is an inappropriate concept for the early modern period, but my aim is to assert its value by shifting attention to ‘responsibilities’ as well as everyday opportunities for exerting some kind of political agency.