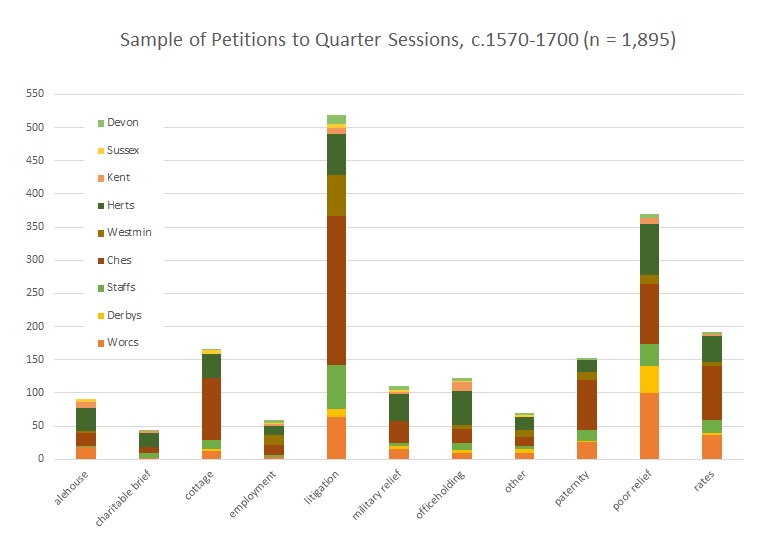

Full transcriptions of 333 local ‘petitions’ from two Midland counties have just been published on British History Online. The first volume includes 239 requests submitted to the magistrates for Staffordshire and the second volume includes 94 to the magistrates of Derbyshire. When added to our recent publication of 572 petitions from Cheshire and Worcestershire, we now have over 900 transcriptions freely available from the late sixteenth to late eighteenth century.

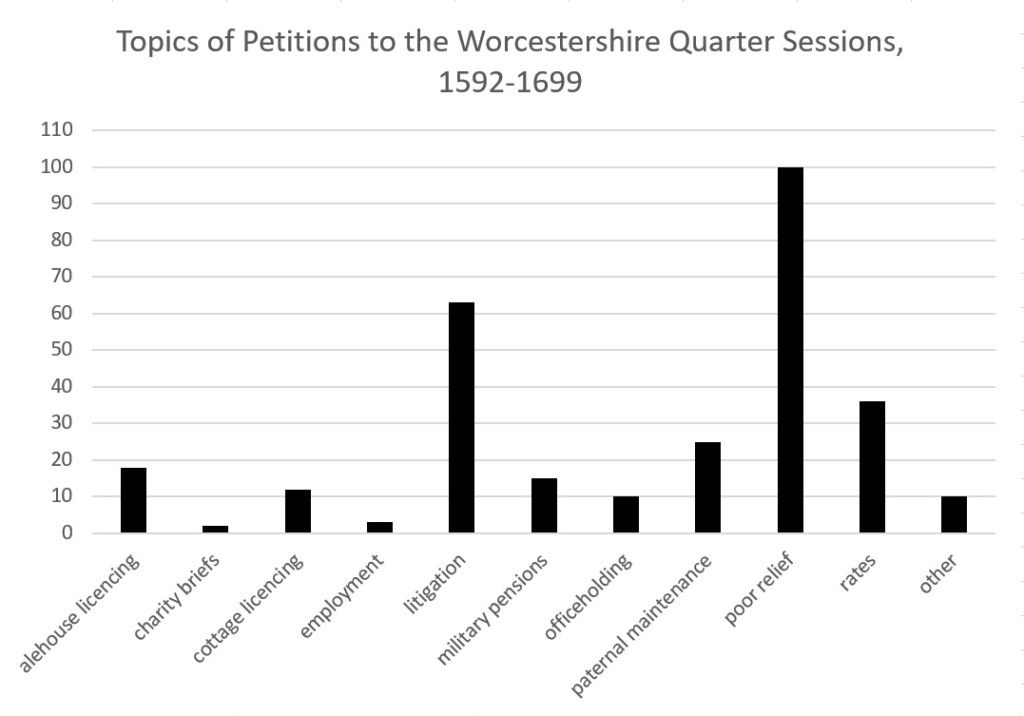

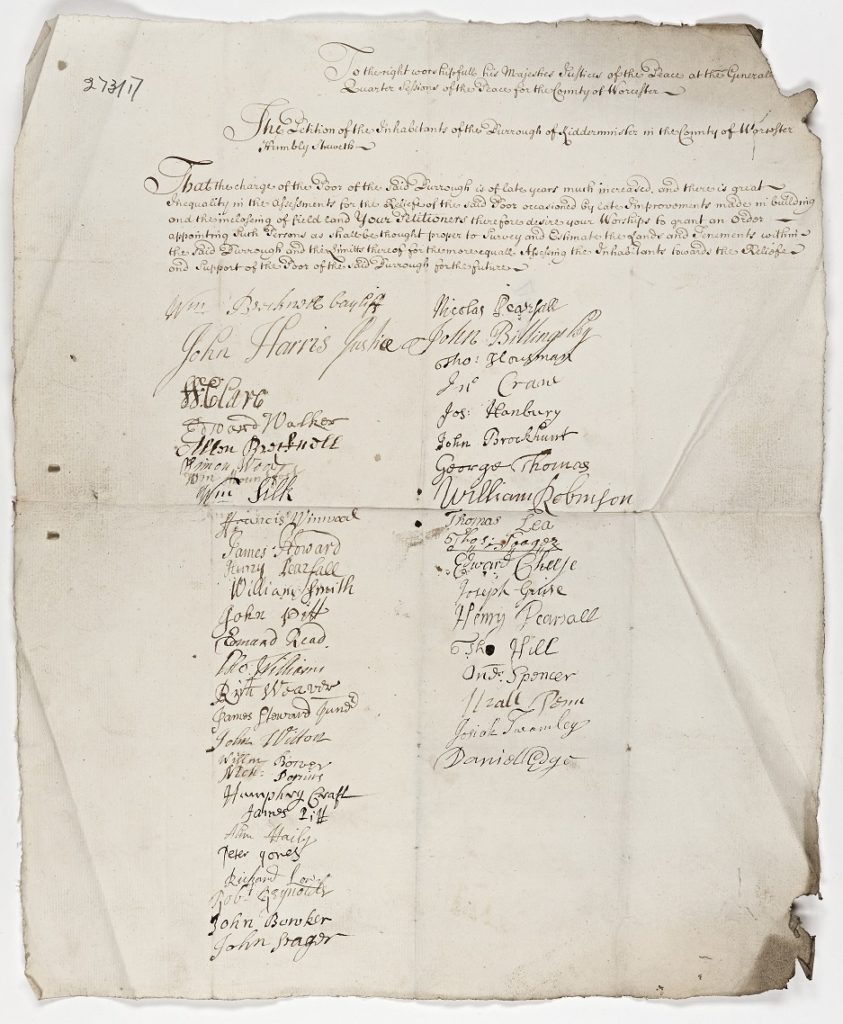

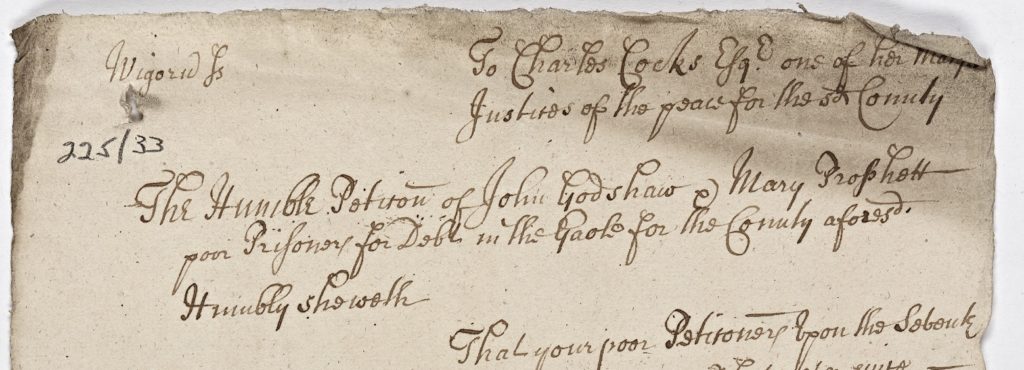

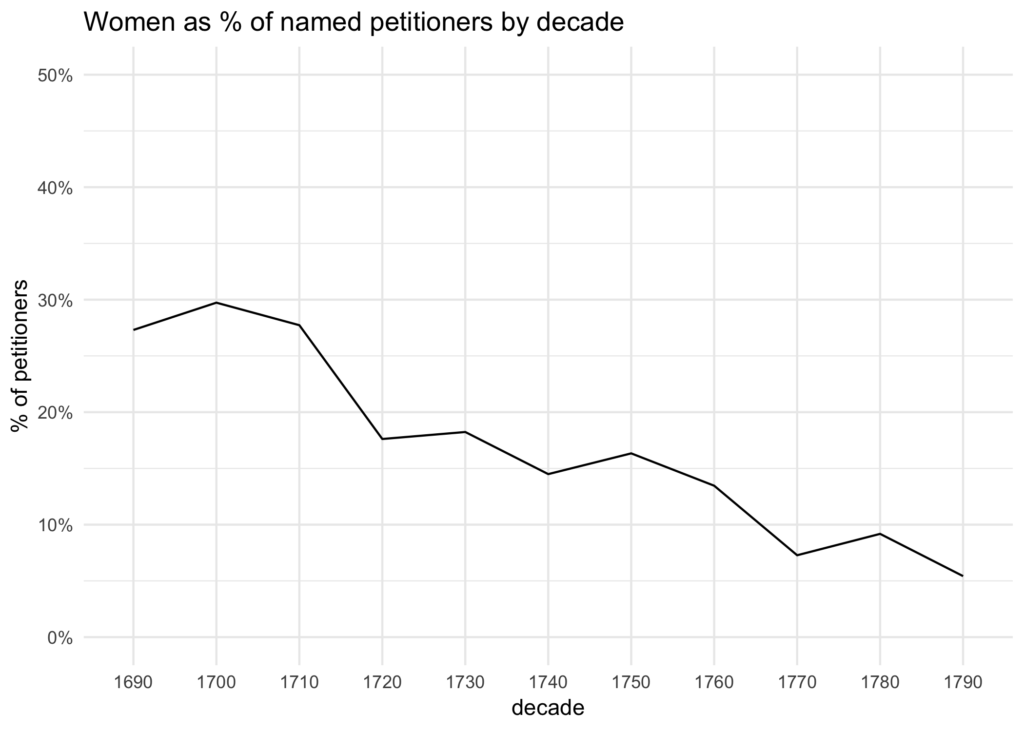

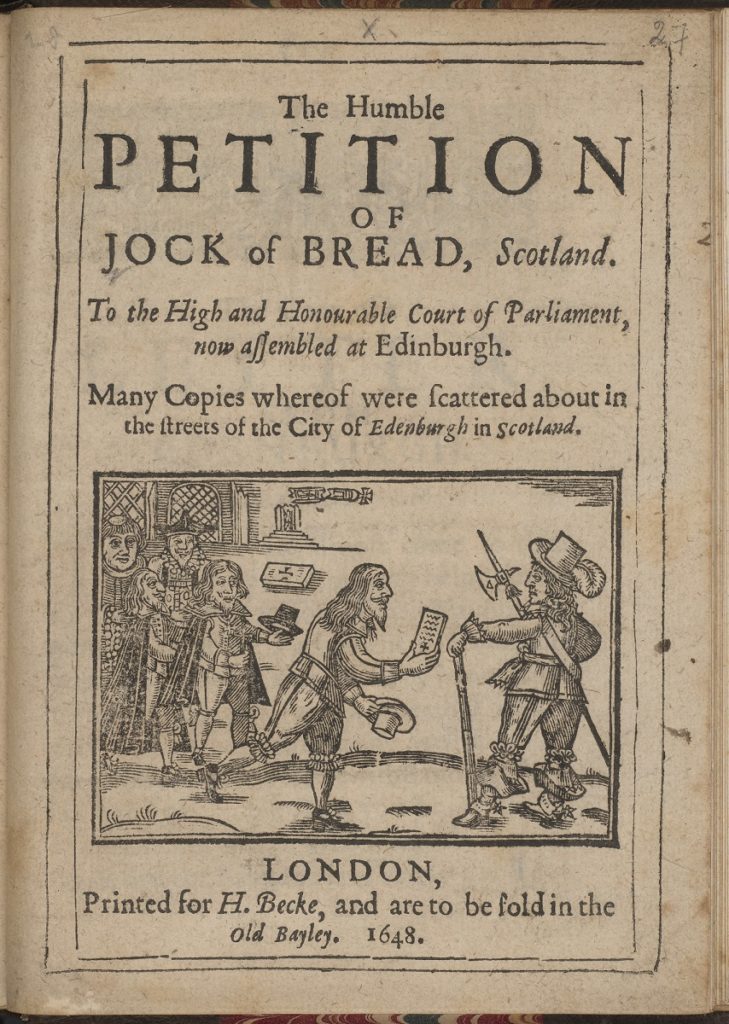

These documents cover a wide range of economic, judicial and other concerns, though they only rarely focus directly on contentious political matters. Most were requests from individuals, both men and women, usually asking for judicial mercy, criminal prosecution, or poor relief. The remainder were from groups such as ‘the poore prisoners in Derby Goale’ who complained of a reduced ‘bare allowance’ for bread in 1680. In the eighteenth century, for the first time, imprisoned debtors began to submit petitions for release under the various Insolvent Debtors Acts and, from around the same time, Protestant Dissenters sought licences to establish meeting houses to worship outside the Church of England.

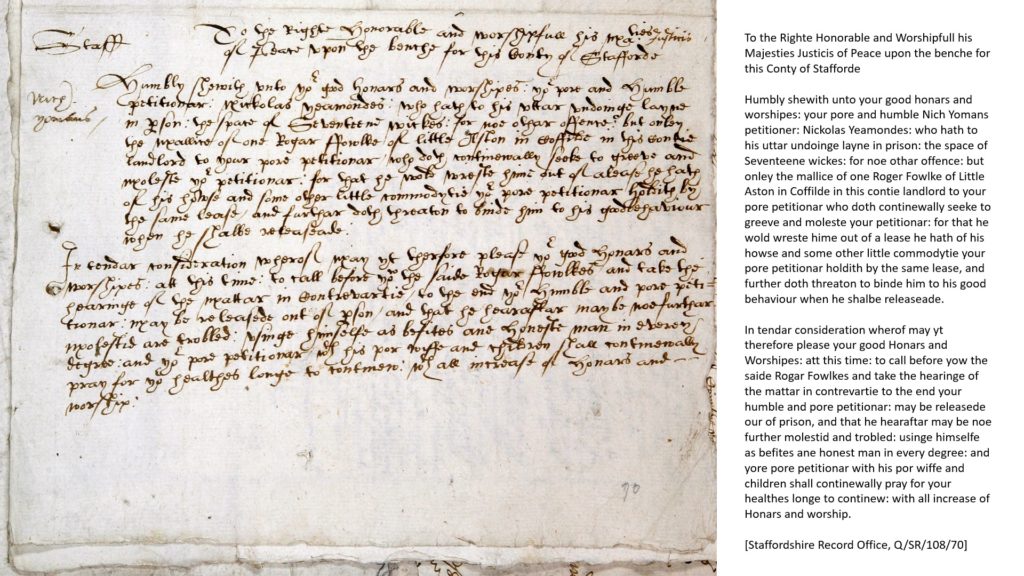

The petition of Nickolas Yeamandes of Staffordshire in 1609 offers an intriguing example of how these requests could potentially counteract the power of local elites. Yeamondes claims he had been imprisoned upon a malicious charge by his landlord, Roger Fowlke of Sutton Coldfield. Apparently Fowlke was using the judicial system to try to force Yeamandes to give up a lease. Yeamandes asks the county magistrates to hold a ‘hearing of the matter in contrevartie’, in the hope that he will be released as ‘ane honest man’. Of course he also promises that he, ‘his por wiffe and children’ will ‘pray for your healthes longe to continew’. Although the full story of this dispute remains to be explored, this document suggests that tenants and other vulnerable individuals might try to use petitioning to overcome the sharp imbalances of power in English society at this time.

If you want to know more about petitioning in early modern England to better understand the context of these documents, you could start by reading our free ‘very short introduction’ and then move on to our ever-expanding annotated bibliography of published scholarship. Each volume also has an editorial introduction briefly reviewing who sent these petitions, the topics covered, their place in the archives, and more. We will be publishing further guidance and advice on our Resources page, but for now just dive into the sources:

- Petitions to the Derbyshire Quarter Sessions, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online (2019)

- Petitions to the Staffordshire Quarter Sessions, 1589-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online (2019)

[Note: Unfortunately the search interface on British History Online is currently not working correctly. To search, rather than browse, the petitions series, you can use google’s ‘inurl’ feature. Simply type inurl:”british-history.ac.uk/petitions” into the search bar, followed by the desired keyword. For example, inurl:”british-history.ac.uk/petitions” debt will return petitions including the word ‘debt’. Apologies for the inconvenience.]

We would love to hear what you find! Remember that searching is currently by keyword only and spelling was very irregular in this period, so you may need to experiment. We will eventually have a more advanced search facility.

These volumes are truely a team effort. The volumes were edited by Brodie Waddell and transcribed by Tim Wales and Gavin Robinson. Preparing the texts for online publication on British History Online was completed by Jonathan Blaney and Kunika Kono of IHR Digital.

We are extremely grateful to Derbyshire Record Office and Staffordshire Record Office who supported the creation of these new transcriptions. We highly encourage readers to take advantage of their extensive collections to pursue further research on the individuals and communities mentioned in the petitions. We are also grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Economic History Society for their financial support, without which these would not have been possible.

The four published volumes are part of a series of seven planned volumes which will also include petitions to the City of Westminster, the House of Lords, and the Crown. We will announce the new volumes here as they appear.