Laura Flannigan

[This post explores the case of two feuding families who submitted a long series of judicial petitions against each other to a variety of different courts. It is written by Dr Laura Flannigan (@LFlannigan17), who is Lecturer in History at Christ Church College, Oxford.]

Petitioning for justice before the highest authorities in early modern England involved decisions and strategies. By the middle of the sixteenth century, numerous royal courts with overlapping jurisdictions were crammed into the legal marketplace of Westminster: Common Pleas, King’s/Queen’s Bench, and Chancery in Westminster Hall itself, and the courts of Star Chamber, Exchequer, Requests, and Wards in adjoining spaces. Why choose one forum over another? On what grounds did litigants and the lawyers they hired make these choices?

Of course, while royal justice was positioned as a last resort and poorer suitors may have been priced out of its costly proceedings, the more resourceful petitioner sued in as many of these forums as possible. To understand why cross-litigating before the Crown was so popular, and why pluralism developed in this jurisdiction at all, we can examine petitions for cases that appeared repeatedly.

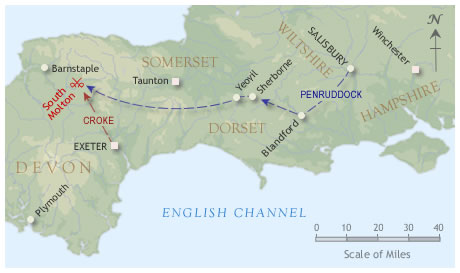

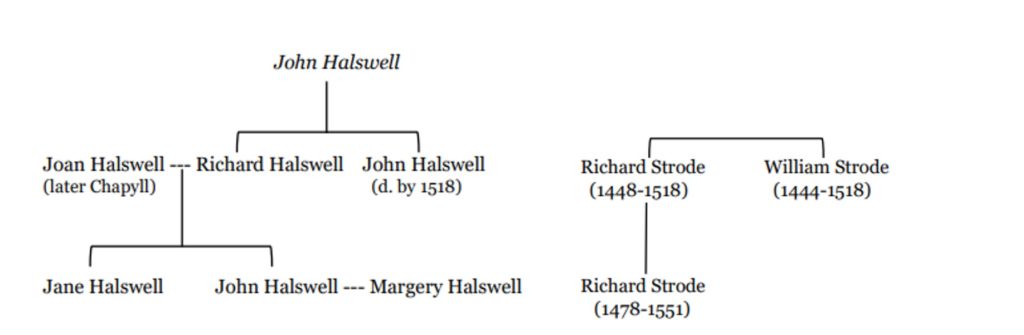

One family feud ran through almost all the central equity courts in the early sixteenth century. Its dramatis personae were the Halswell and Strode families, hailing from Devon. The gentry family of Strode from Plympton St Mary was headed by the elderly William Strode and his brother Richard until both of their deaths in 1518, and thereafter by Richard’s son, also called Richard. Men of considerable standing in the county, they acted as local officials and both Richards sat as MP for Plympton Erle. In managing their estates, they were voracious users of the law. All three men appear regularly in both the central common-law courts and in the equity courts, as petitioners and defendants in suits with their tenants.

Leading the Halswells of Dartmouth were the brothers John and Richard, Richard’s wife Joan, and their children, John and Jane. The Halswells left little trace in the historical record, so were presumably poorer than the Strodes. John Halswell senior had sold his lands to make up for various debts owed and was described at one point as a ‘common land seller’. But the younger John Halswell was said to be a ‘yeoman’ and was able to hire a serjeant at law as his legal counsel.

The dispute between them produced at least seventeen separate suits, with twelve surviving petitions in the central archives.[1] Taken together, they illustrate the perceived differences in the character of each royal court and the strategies adopted when petitioning to them. Continue reading “A Family Feud and Parallel Petitioning to the Crown from Sixteenth-Century Devon”