To the right honnorable the Earle of Salisbury Lord High Threasurer of England.

The humble peticion of Marey Carliell widdowe late wife of Christopher Carliell governour of Nocfergus in Ireland deceased.Shewing, that aswell in consideracion of her said husbandes faithfull services, as allso of 150 pounds then owing him by her late majestie, it pleased her highnes to promise him the benifitt of such landes as should fall unto her majestie by the attainder of one William Vaux which was prosecuted by her said husband to his charge of 400 pounds at the leaste, and so died before her majesties promise was effected.

That the said Vaux stood bounden in a statute staple of 2500 pounds unto her husband for payment of 1300 pounds.

That the said Vaux by the only meanes and charge of her said husband, did leavie fines and suffer recoveries, whereby Vauxs his landes being formerly intayled and so not lyable to the attainder, became chargeable to the statute and subject to the attainder.That this your suppliant was a long suitor both unto the late Queene, and ever since to Kinges majestie, for a graunt of the inheritance of the said land.

That the consideracion of her said suite was by his majestie referred to the late Lord Threasurer, who deceased before he did any thing therein: and therefore is enforced to become a new suitor unto his majestie againe, eyther to be pleased to confirme the inheritance as our gratious Queene Elizabeth promised, or ells his majesties free leave to extend the statute made by Vaux to her said husband, and so humbly beseeching your honors favour and furtherance in respect of a poore widdowe unable to attend.

[Paratext:] 21 January 1608. For the first part of this gentlewomans suite I have nothing to do with all, neither (yf there were any such promise as shee pretendes) hath shee any reason to prefer it now considering his majesty, (who is tyed in honor to performe no other promises then his owne) hath otherwise disposed of the land. But for the statute, which shee desires leave to extend upon the land, yf by lawe shee may do it, shee needes sue for no licence. R Salisbury

Report of Virginia Gingell

In summary, Mary Carleill, the widow of Captain Christopher Carleill, petitioned the Earl of Salisbury, the Lord High Treasurer to James I, for a grant of inheritance of lands, previously owned by William Vaux and subject to an attainder, that, she claimed, had been promised by Elizabeth I to her late husband in consideration of his faithful service and the sum of £150 owed to him by the Queen or for leave to extend the statute staple, prosecuted by Christopher Carleill which, she claimed, had required Vaux to make a payment to her husband of £2,500.

Mary Carleill also claimed that this matter had been previously referred by James I to the former Lord Treasurer, who had since died.

Very little is known about Mary Carleill – other than in relation to Christopher Carleill – and it is for this reason that these notes start with the life of her husband.

Christopher Carliell, usually spelt Carleill, c 1551 -1593

Christopher Carleill was a distinguished soldier and a naval commander, an adventurer, writer, friend of the poet Edmund Spenser, advocate of the colonisation of America[1] and, at the end of his career, governor of Ulster. During his lifetime it was also reputed and disputed that he had been involved in piracy.

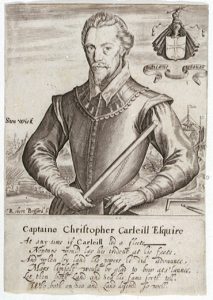

This engraving by Robert Boissard (Q 1570 – 1603), in the National Maritime Museum collection, bears the legend: ‘Captaine Christopher Carleill Esquire. At any time if Carleill led a fleete Neptune would lay his trident at his feete, And when by land his powers he did advance, Mars himself would be glad to bow ats Launce. Let them both land and sea his fame forth tell, who both on sea and land deserv’d so well.’ [2]

His life is well documented and the following is drawn mainly from entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and a biography by R Lloyd, published in 1974, entitled Elizabethan adventurer: a life of Captain Christopher Carleill.

Family background

Christopher Carleill was born in London to a wealthy family and was the eldest son of Alexander Carleill (1526-1561) and Anne Barne (1528-1564).

His father Alexander was the son of Alexander Carleill (1503-1555), ‘Lord of Brydekirk’ and Sybill Carruthers (born 1500), both from Dumfriessshire. Christopher’s father was one of the Charter members of the Muscovy (later Russia) Company, a Master of the Vintners Company in 1561 and a freeman of the Mysteries of Vintners in the City of London. A monument to him in St Mary Pater Noster Church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666.[3][4]

His mother Anne Barne was the youngest of four children, the daughter of Sir George Barne (c1500-1558) and Alice Brooke (1504-1599). Sir George Barne, his maternal grandfather, was a City of London merchant, knighted in 1553, and served as Sheriff of London 1545-6 and Lord Mayor of London 1552-3. He was a member of the Haberdashers’ Company, a founder member of the Muscovy Company, promoted the first expedition of the Company of Adventurers to the New Lands and an expedition to West Africa.[5] [6]

Christopher Carleill’s sister Alice (1535-1602) married Sir Christopher Hoddesdon (1533/4-1611), a wealthy merchant, also a member of the Muscovy Company, who developed trade with North East Europe and Russia, on behalf of the company and the Queen and, by 1600, was Master of the Merchant Adventurers Company.[7]

Following the death of his father in 1561, Christopher Carleill’s mother married Sir Francis Walsingham (1532-1590), Principal Secretary to Elizabeth I from 1573 and a Privy Councillor. His mother died three years later and Sir Francis Walsingham assumed the care of Christopher Carleill, who enjoyed the support and patronage of his step-father throughout his career.

In 1566 Sir Francis Walsingham married Ursula St Barbe (1532-1602). Their daughter Frances (1569-1632), a lady in waiting to Queen Elizabeth I, was married three times: firstly to Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586) and, on his death, to Robert Devereux, the 2nd Earl of Essex and the stepson of Robert Dudley (1556-1601), Earl of Leicester, who was beheaded for treason in 1601. By the time of her third marriage to Richard Burke (1572-1635), Earl of Clanricarde, an Irish nobleman, Frances and her husband were described as recusants, who had been granted immunity from prosecution by James I and Charles I, for practising their faith as Roman Catholics.[8]

Christopher Carleill’s professional life

Much is known about Christopher Carleill’s adult life – described in his biography by R. Lloyd. He went to Cambridge University and was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn. In 1573 he joined an English regiment to assist the Dutch Protestants in the Netherlands against the Spanish, remaining there until 1577. He later fought for the Huguenots in France before returning to the Netherlands where, between 1580 and 1581, he acted as second in command to Sir John Norris, ‘the most acclaimed English soldier of his day’, [9] with whom he had also fought in France.[10]

Following a successful mission to Russia in 1582, as commander of a fleet of eleven ships providing an escort to the Muscovy merchants acting in the service of the Queen, he attempted and failed to secure sufficient funding to establish a plantation in North America.[11]

At a time of unrest in Ireland and concerns about an imminent invasion by the Scots, Christopher Carleill was appointed commander of the garrison at Coleraine, Co. Antrim in 1584, a post he held briefly before being recalled following disputes with Sir John Perrot, the Lord Deputy of Ireland.[12]

When, in 1585, Sir Francis Drake led an expedition to attack Spanish colonies in the West Indies, Christopher Carleill was appointed lieutenant -general of his land forces, comprising of more than 2,300 troops and captained the Tiger, one of a fleet of twenty one ships (the numbers differ in different accounts). The voyage lasted ten months and resulted in the capture and destruction of parts of Santiago, in the Cape Verde islands, Santo Domingo in what is now the Dominican Republic, Cartagena in Columbia and St Augustine on the coast of Florida. A ransom of 25,000 ducats was required to be paid in Santo Domingo and 110,000 ducats in Cartagena. [13] [14]

Christopher Carleill returned to Ireland in 1588, serving firstly as governor of Nocfergus, now known as Carrickfergus, at the time of the Spanish Armada, and then Ulster. He remained there until the summer of 1592, apart from a recall in 1589 to report on the fortifications at Ostend, and then came back to London and died the following year on the 11th November 1593.

He was awarded a Grant of Arms in 1593 in the name of Christopher Carlisle of the County of Cumberland, having traced his family back to a William de Carleill in Cumberland in the reign of Edward I.[15] His memorial, describing his achievements, is reproduced in Latin in ‘Collections for a history of the ancient family of Carlisle.’ [16]

Mary Carleill, the petitioner

Little appears to be recorded about Mary Carleill although it is believed that she was not a noble woman and that the marriage took place sometime in or before 1588. [17]

In some early sources[18] Walsingham is described as Christopher Carleill’s father-in-law, the contemporary term used for step-father. This has led to the suggestion that Carleill married Walsingham’s daughter Mary (1572-1580) who died in childhood; this would appear to be incorrect.

There is a 1608 reference to two daughters the marriage: Frances and Mary.[19] In another document, however, the children’s names are given as Mary and Francis.[20]

To date it has not been possible to determine where or when Mary Carleill was born or died, the names of her parents, any other details about the children, or of her life as the wife and widow of Christopher Carleill. In 1592, a year before his death, she was living in St Botolph’s Lane, in London.[21]

The Decline in the Carleill family finances and attempts over the years to seek financial assistance from the Crown

It would appear that throughout his career Christopher Carleill had experienced difficulty in being reimbursed for his services as a soldier and naval commander. It is reported that during the first period he spent fighting in the Netherlands he did so at his own expense and that a request, made in 1580, for reimbursement of 5,000 guilders for expenditure on ammunition, was still a matter of dispute four years later.[22] [23]

When Christopher Carleill was first in Ireland in 1584, Sir John Perrot , the Lord Deputy of Ireland refused to provide munitions and money to cover food and clothing for his troops[24] and in 1586, nearly a year after his return from Drake’s expedition to the West Indies, he was still claiming £400, his share of the profits, and was awarded only £280.

His second appointment in Ireland in 1588 came with a salary of £300 a year but there were delays and other difficulties relating to payment – leading to the accumulation of debts. [25]

Following a reduction in pay from sterling to Irish pay, in 1588, a complaint was made to the Privy Council by Christopher Carleill, Sir Richard Bingham, a soldier and Lord President of Connaught 1584 – 1597, and Captain Egerton, governor of Carrickfergus Castle, who had been forced to sell some of his estate in England to raise money to feed his soldiers. Payment was restored in 1589, but, sometime later, in March 1590/91, Christopher Carleill was at Court with others seeking to recover debts incurred in Ireland [26]

Sir Francis Walsingham, Christopher Carleill’s stepfather, who had provided financial assistance when he was in Ireland, died on 6 April 1590, after a period of illness, leaving a debt to the Queen of £42,000, an annuity to Frances, his daughter and his goods to his wife.[27]

Two months later, on 10 June 1590, Christopher Carleill wrote to Lord Burghley requesting a commission from the Queen to seize goods in England belonging to Spanish subjects, stating that this was the practice when goods were seized on the high seas, with the Lord Admiral retaining one tenth of their value. In this letter he argued that this would ‘relieve my moste ruined and distressed estate withal, as in a man’s lifetime will hardly happen to such another…’, .pleading ‘I have bene longe tyme a fruiteles suitor, even well nighe the moste part of fower yeares tyme, as also that I have spente my patrimonye and all other meanes in the service of my countreye, which hath not been less than five thousande pounds, whereof I doe owe at this presente the beste parte of 3,000. There is no man canne challenge me that I have spente any part of all this expense in riotte, game, or other excessive, or inordinate manner.’ He suggested that this would result in profit for the Queen and himself; and would provide the only opportunity to settle his estate for himself ‘and my poor wife and children….‘.

Christopher Carleill had previously approached Queen Elizabeth I in 1589 with this proposal, but the goods in question had left the country before a decision was made.[28] [29] [30]

In July 1592/3, Mary Carleill wrote to Lord Burghley, Lord Treasurer, requesting part-payment of about £1,000 which, she claimed, was due to her husband by warrants signed by the Lord Deputy and Council in Ireland and held by Sir Henry Wallop (1540 -1599), a member of the Irish Parliament, Vice-Treasurer of Ireland from 1579 to 1582 and Lord Justice from 1582 to 1584.[31] [32] [33] It is not known when these warrants were signed: Sir John Perrot was Lord Deputy of Ireland from 1584 to 1588 and was tried for high treason in April 1592. He was succeeded by Sir William FitzWilliam (1526 – 1599) who served in Ireland until 1594.

Sometime in 1592, money was provided to meet Irish debts and Christopher Carleill received £50 and was allowed to return to England.[34] Also in 1592, Christopher Carleill was granted land or perhaps was offered a possible grant of land by the Queen that, it was anticipated, would be confiscated following the conviction of a William Webb of Salisbury for murder.[35] This however did not happen and Christopher Carleill wrote to Elizabeth I repeating an earlier request for the grant of a reversion of fifty years in a hundred acres of Duchy land pleading: ‘as a man consumed, fallen and desperate must I beseech your leave to withdraw myself from the unsupportable shame which already begins to fall on me…’.[36]

Christopher Carleill died in November 1593. There were disagreements over the will. [37] In 1594 Mary Carleill took over the administration of Alexander Carleill’s estate for the benefit of their children, and on 17 April 1596, she was granted administration of Christopher Carleill’s estate, which she had initially renounced, and inherited less than £20.[38]

The attainted lands of William Vaux of Catterlen

This petition concerned the attainted lands of a William Vaux which, Mary Carleill claimed, had been promised to Christopher Carleill by Queen Elizabeth I, on his payment of £400, but that he had died before the grant of land was made. She also claimed that William Vaux had been bound by a statute staple that had required him to make a payment to Christopher Carleill of £2,500, in consideration of her husband’s payment of £1,300. The date of the statute staple is not known but would have been before Christopher Carleill’s death in late 1593.

The grant of the attainted lands to Mary Carleill and subsequent transfer of title

What is known is that on 19 February 1594, three months after Christophe Carleill’s death, Queen Elizabeth I, granted a lease of Catterlen manor and other attainted lands of William Vaux, to Mary Carleill, and Frances and Mary Carleill during their life time. [39]

Mary Carleill took over the estate on 28 April 1594. Two years later, her interest was sold to a Richard Hutton, and the estate then passed to a John Musgrave, reverted to the Crown on his conviction for felony and a 40-year lease was then granted by King James I to John Murray, one of the Grooms of the Bedchamber in 1608. [40][41]

The following sets out what has been found about William Vaux and his family and what has been found about the events that led to the confiscation and subsequent transfer of his lands during the period between 1590, when William Vaux died, and 1609, the date of the petition. It includes notes on Richard Hutton, barrister, and identifies some of the links between the local Vaux, Hutton and Musgrave families.

The main sources are Ancestry, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Landmark Cases in Criminal Law, edited by Philip Handler, Henry Mares and Ian Williams, 2017, the History of Parliament website and National Archives catalogue notes to original documents, available in the Archives, that have not been digitised or, as far as is known, transcribed.

William Vaux of Catterlen c.1555-1590: Family background and the circumstances leading to the confiscation of his land

The manor of Cattlerlen, next to Plumpton, a few miles from Penrith in Cumberland, was granted to Hubert Vallibusor/Vaux by Henry 11,[42] although there is a record that Catterlen was the home of Sir Edward Musgrave in about 1480.[43]

William Vaux was the eldest surviving son of Rowland Vaux (1535-1587), Lord of the Manor, who built Catterlen Hall in 1577, and Anne Salkeld (1535 – 1588), the daughter of Thomas Salkeld.[44] He came from a large family and Jane, one of his sisters, married Sir William Hutton of Hutton Hall in Penrith, the brother of Sir Richard Hutton.[45]

William Vaux was married to Mabel(l) (died 1609) and they had one son John (1583–1650) who, in 1615, married Lady Isabel Musgrave (1579-c1650), the daughter of Sir Edward Musgrave of Hayton Castle, sometimes referred to as Brayton.

William Vaux was a barrister, a member of Gray’s Inn from 1573 and was called to the Bar in 1581. His lands were attainted following his conviction for the murder of his friend Nicholas Ridley of Willimoteswick, Haltwhistle, Northumberland, who was the sheriff of the county at the time of his death in 1585. It was known that William Vaux stood to inherit land worth £100 on his friend’s death. [46]

Nicholas Ridley (1551–1585) was the eldest son of Sir Nicholas Ridley (1527–1574) and Lady Mabel Dacre (1522–1573) and was probably related to Nicholas Ridley (1502-1555), Bishop of London and Protestant martyr, who was also born in Willimoteswick. Nicholas Ridley and his wife Margaret, the daughter of Thomas Forster, were childless and, on the recommendation of William Vaux, Nicholas Ridley took cantharides, a highly toxic aphrodisiac and died. [47]

William Vaux was tried at Newcastle Assizes in August 1588 and was acquitted of murder. He was brought before the court again in July 1590, was found guilty by the King’s Bench (R v Vaux 1591) and was hanged. For different reasons, both verdicts were considered unsatisfactory. [48]

His counsel was a Richard Hutton, a member of Gray’s Inn, admitted in 1580 and called in 1586, with a Cumbrian practice. [49] He was almost certainly Sir Richard Hutton (c1561-1639), member of Gray’s Inn with the same dates of admission and call. Sir Richard Hutton was the son of Anthony Hutton (died 1590) of Hutton Hall, where the family had lived since 1272 and Elizabeth Musgrave of Hayton Castle, Cumberland.[50] He was married to Agnes Briggs (died 1648), his brother Sir William Hutton was married to William Vaux’s sister Jane and his youngest daughter married Sir Philip Musgrave in 1625.

Sir Richard Hutton was well-connected and achieved high office. He had a London Equity practice where he represented many Northern tenants,[51] was appointed a Serjeant at Arms in 1603, a member of the Council of the North, a judge and Justice of the Common Pleas at Westminster.

In 1592 he moved to Goldesburgh, Yorkshire, and bought lands in Cumberland, Westmoreland and Yorkshire. Later in life he was found not guilty of high treason and his accuser was ordered to pay £10,000 for defamation of character.[52]

The transfer of the Cattlerlen lands

The National Archives holds some documents, which have not been digitalised, relating to the transfer of these lands – including inquisitions into the attainted possessions of William and Rowland Vaux undertaken in 1588 and 1603. [53]

Two years after the grant of the lands to Mary Carleill in 1594, there are two National Archives documents relating to the purchase of Mary Carleill’s interest in the autumn of 1596 by Richard Hutton, the barrister who had acted as counsel for William Vaux and whose mother was a member of the Musgrave family.[54] Nothing has been found about the circumstances leading to this transaction: did Mary Carleill approach Richard Hutton with the intention of selling her interest or for assistance in obtaining the £2,500 she claimed was due under the statute staple? – or – was Richard Hutton acting on behalf of the Musgrave family?

The Musgraves were a prominent local family. Sir Richard Musgrave (1582-1615) of Hartley Castle, Westmoreland and Eden Hall Cumberland was MP for Westmoreland in 1604 and the head of a Westmoreland family that went back to the time of Henry II. He was the son of Sir Simon Musgrave, Constable of Bewcastle and nephew of Sir Richard Musgrave of Norton Conyers, Yorkshire. Another branch of the Musgrave family was headed by William Musgrave, of Hayton Castle, Cumberland.[55]

John Musgrave (c1579–1608), most probably the fourth son of Sir Simon Musgrave of Edenhall and the uncle of Sir Richard Musgrave of Hartley Castle and Edenhall, was married to Isabel. In 1598 he had been granted, inter alia, the castle and manor of Askerton and in 1606 was living at Plumpton. [56]

In January 1607, Richard Craven, Deputy Receiver for Cumberland and Westmoreland, Collector of the King’s revenues, was robbed of over £200 on the road between Penrith and Kendal. It was alleged that this robbery was planned at Edenhall, the home of Sir Richard Musgrave (1582-1615) of Hartley Castle, Westmoreland and Eden Hall Cumberland.

Those charged with the robbery included John Musgrave, Thomas Musgrave, son of Sir Richard Musgrave of Norton Conyers, Yorkshire, who was later pardoned, Christopher Pickering of Crosby, Ravensworth and Randall Bell. [57]

John Musgrave was judged to be the instigator, was executed for felony, and his lands attainted. These events are commemorated in a ballad called ‘The Lamentation of John Musgrave’.[58] [59] An early copy in the British Library (not seen) has two illustrations: one of John Musgrave in his finery, the other on the gallows.[60]

In May 1608, King James I granted Catterlen to John Murray, who, in 1605, had been granted the nearby estate of Plumpton Park, on a forty-year lease against the wishes of the Musgrave family: a lease on the estate had been earlier granted by Queen Elizabeth I to Sir Simon Musgrave and his son, Sir Thomas Musgrave, for life. [61]

John Murrray,[62] [63] 1st Earl of Annandale (died 1640) was a Scottish courtier, a Groom to the Bedchamber from 1603 to 1622, Keeper of the Privy Purse from 1611 -1625 and MP for Guildford in 1621.

It would seem that the Musgrave family did not immediately relinquish Catterlen Manor and other Catterlen lands to John Murray. In 1609 a case was brought by the Attorney General acting on behalf of John Murray, against Isabel Musgrave, John Musgrave’s widow, and James Bellassis.[64]

An interlocutory order was granted in May 1609 [65] and later that year there is a document in the National Archives relating to what appears to be another hearing or case brought by the Attorney General on behalf of John Murray against Isobel Musgrave, concerning the right and title to the lordship of Catterlen and other lands. [66]

The outcome of this case is not known but there is a later record of an action brought in 1616 by John Murray, Groom of the Bedchamber against Sir Richard Musgrave, Isabel Musgrave, Francis Jones, Alderman of London and others relating to the forgery of a conveyance of the manor of Cutterden (Chatterlyn) and the rescue of Isabel Musgrave from arrest. It seems very likely that this relates to the manor of Catterlen. [67]

Mary Carleill’s petition

This petition raises many questions.

Whilst it has been possible to trace the transfer of the Catterlen lands from the execution of William Vaux in 1590/91 to the date of the petition, no records have been found relating to the earlier statute staple, nor of any steps Mary Carleill may have taken to try and recover the £2,500 that she claimed was due to her. In her petition she states that she had previously approached the former Lord Treasurer – but the date of this is also not known.

It is difficult to tell from the wording of the petition whether Mary Carleill had been aware that Catterlen Manor and other lands had been granted to her and her daughters by Elizabeth I in 1594.

If she had known, then it is possible that she may not have known or understood that her rights in respect of these lands had been relinquished when, two years later, Richard Hutton purchased her interest.

It also seems possible that the grant of the Catterlen lands may have included lands previously subject to the statute staple and that these rights had also been extinguished: the documents in The National Archives, which have not been read, might provide information about these transactions that does not appear to be recorded elsewhere.

In this petition, so many years after her husband’s death, Mary Carleill describes herself as a ‘poore widowe unable to attend’ and maybe poverty or infirmity and the reversion of the Catterlen lands to the Crown, following the execution of John Musgrave, caused her to try and reassert a right that she no longer had.

Whatever had led to her petition however, it would seem that it was bound to fail.

Response of the Earl of Salisbury, Lord High Treasurer

In respect of the first part of the petition relating to the claim that attainted lands belonging to William Vaux had been promised by Elizabeth I: the Earl of Salisbury ruled that this was not a matter for him to consider, and that if such a promise had been made, James I, who was bound only by his own promises, had disposed of the land.

In respect of the second part relating to her request for leave to extend the statute staple: the Earl of Salisbury ruled that if Mary Carleill had a legal right to seek to an extension, she needed to sue for no licence.

With thanks for advice to Dr Brodie Waddell, Birkbeck, University of London, Academic Advisor to the U3A Shared Learning Project, and Dr Amanda Bevan, Head of Legal Records, The National Archives.

Please note that in this report, ‘Carleill’, the more common spelling of the surname has been used, and some discrepancy has been found in some of the dates given in various sources – which should be regarded therefore as approximate.

References

[1] Trim, D. J. B. “Carleill, Christopher (1551?–1593), soldier and naval commander”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sep. 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-4668; Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Carleill

[2] National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/106528.html

[3] Ancestry.co.uk

[4] Nicholas Carlisle, Collections for a history of the ancient family of Carlisle (1822), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101063057127 (includes the inscription in Latin)

[5] Slack, Paul. “Barne, Sir George (c. 1500–1558), merchant and local politician.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-37157

[6] Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Barne_II

[7] Hodsdon, James. “Hoddesdon, Sir Christopher (1533/4–1611), merchant.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-13417.

[8] Adams, Simon, Alan Bryson, and Mitchell Leimon. “Walsingham, Sir Francis (c. 1532–1590), principal secretary.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-28624

[9] Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Norris_(soldier)

[10] ‘Carleill’, ODNB

[11] R Lloyd, Elizabethan adventurer: a life of Captain Christopher Carleill (1974)

[12] ‘Carleill’, ODNB

[13] Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Drake#Great_Expedition_to_America

[14] Hans P. Kraus, Sir Francis Drake: A Pictorial Biography (1970): https://www.loc.gov/rr/rarebook/catalog/drake/drake-6-caribraid.html

[15] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[16] Carlisle, Collections for a history of the ancient family of Carlisle

[17] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[18] For example: J. Hall Pleasants, ‘The Lovelace Family and its connections’ (1921) https://archive.org/stream/jstor-4243807/4243807_djvu.txt

[19] ‘Cecil Papers: May 1608’, in Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House: Volume 20, 1608, ed. M S Giuseppi and G Dyfnallt Owen (London, 1968), pp. 151-177. British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-cecil-papers/vol20/pp151-177

[20] TNA catalogue note: Attorney-General, By John Murrey v Isabel Musgrave, Ref E 134/7Jas 1/Mich 17 1609

[21] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[22] ‘Carleill’, ODNB

[23] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[24] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[25] ‘Carleill’, ODNB

[26] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[27] ‘Walsingham’, ODNB

[28] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[29] Carlisle, Collections for a history of the ancient family of Carlisle

[30] ‘Carleill’, ODNB

[31] Fritze, Ronald H. “Wallop, Sir Henry (c. 1531–1599), administrator and member of parliament.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-28580

[32] ‘Elizabeth I: volume 166, July 1592’, in Calendar of State Papers, Ireland, 1588-1592, ed. Hans Claude Hamilton (London, 1885), pp. 537-564. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/ireland/1588-92/pp537-564.

[33] ‘WALLOP, Sir Henry (c.1531-99), of Farleigh Wallop, Hants.’, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558-1603, ed. P.W. Hasler, 1981, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/wallop-sir-henry-1531-99

[34] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[35] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[36] Cited in Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[37] There is a reference in Matthew Woodcock, ‘The New Poet and the Old: Edmund Spenser and Thomas Churchyard’, Spenser Review 48.1.4 (Winter 2018), http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/spenseronline/review/item/48.1.4, but no details are given.

[38] Lloyd, Elizabethan Adventurer

[39] Calendar of Patent Rolls 36 Elizabeth I (1593-1594) C66/1405 -1424, volume 39 List and Index Society, 2005, edited by Simon Neal. The National Archives also have two Privy Seal warrants dated January 1594 (C82/1563) and February 1594 (C82/1564)

[40] ‘Cecil Papers: May 1608’, in Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House: Volume 20, 1608, ed. M S Giuseppi and G Dyfnallt Owen (London, 1968), pp. 151-177. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-cecil-papers/vol20/pp151-177.

[41] Richard Hutton v Mabel Vauxe and others: The manor of Catterlen and other lands: The National Archives, E133/8/1215 (catalogue note).

[42] Daniel Lysons and Samuel Lysons, ‘Parishes: Newton-Regny – Ponsonby’, in Magna Britannia: Volume 4, Cumberland (London, 1816), pp. 142-150. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/magna-britannia/vol4/pp142-150

[43] Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmoreland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society (volume 15 No 1), p. 8

[44] Old Cumbria Gazetteer

[45] Samuel Jefferson, The history and Antiquities of Cumberland (1840), p. 148

[46] Philip Handler, Henry Mares and Ian Williams (eds), Landmark Cases in Criminal Law (2017)

[47] Philip Handler, Henry Mares and Ian Williams (eds), Landmark Cases in Criminal Law (2017)

[48] Philip Handler, Henry Mares and Ian Williams (eds), Landmark Cases in Criminal Law (2017), chapter by John Baker entitled ‘R v Saunders and Archer (1573)’ for a discussion of the legal issues and notes on cantharides.

[49] Philip Handler, Henry Mares and Ian Williams (eds), Landmark Cases in Criminal Law (2017)

[50] Prest, Wilfrid. “Hutton, Sir Richard (bap. 1561, d. 1639), judge.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-14311.

[51] R.W. Hoyle, ‘Lords, Tenants and Tenant Right in the Sixteenth Century: Four Studies’, Northern History, volume 6 (1971)

[52] ‘Hutton’, ONDB

[53] TNA catalogue note: Cumberland: Inquisitions as to the possessions of William and Rowland Vaux, TNA E 178/585 (30 and 44 Eliz 1), http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C5141781

[54] TNA catalogue notes: Richard Hutton v Mabel Vauxe and others etc TNA E 133/8/1215, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C5921913; and Richard Hutton v Mabel Vauxe and others, E 134/37-38E Eliz/Mich/6.

[55] ‘MUSGRAVE, Sir Richard (1582-1615), of Hartley Castle, Westmld. and Eden Hall, Cumb.’, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629, ed. Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris, 2010, http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1604-1629/member/musgrave-sir-richard-1582-1615

[56] Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmoreland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society (http://www.ebooksread.com/authors-eng/cumberland-and-westmorland-antiquarian-and-archol/transactions-of-the-cumberland–westmorland-antiquarian–archaeological-society

[57] Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmoreland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society

[58] Rollins, Hyder E. “Notes on the ‘Shirburn Ballads.’” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 30, no. 117, 1917, pp. 370–377.

[59] English Broadside Ballad: University of California: Santa Barbara Archive https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/20779/xml for the full text of the ballad.

[60] Execution Ballads, https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/execution-ballads/items/show/911

[61] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-border-papers/vol2/pp930-933)

[62] ‘MURRAY, John (-d.1640), of Lochmaben, Dumfries; St. Martin’s Lane, Westminster and Guildford Park, Surr.’, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629, ed. Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris, 2010, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/member/murray-john-1640

[63] ‘James I: Volume 31, January-March, 1608’, in Calendar of State Papers Domestic: James I, 1603-1610, ed. Mary Anne Everett Green (London, 1857), pp. 393-420. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/jas1/1603-10/pp393-420

[64] Attorney-General, on behalf of John Murrey v Isabell Musgrave: Manor of Catterlen TNA E134/7 Jas1/Hil 13. The National Archive catalogue note details the manors, granted by Queen Elizabeth to Mary Carleill and others, and ‘conveyed by her to Mr Serjeant Hutton’ i.e. Richard Hutton, serjeant-at-law.

[65] https://uh.edu/waalt/index.php/E124-6_for_1603-1613

[66] TNA catalogue note: Attorney -General by John Murrey v Isabell Musgrave: Right and title to the lordship of Catterlen and messuages in six other places. (TNA E134/7Jas1/Mich17).

[67] Murray v Musgrave, TNA STAC 8/209/18.

This report is part of a series on ‘Petitioners in the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, 1600-1625’, created through a U3A Shared Learning Project on ‘Investigating the Lives of Seventeenth-Century Petitioners’.