The leatherdressers of the borough of Southwark. SP 14/127 f. 30 (1622)

To the right worshipfull Sir Robert Heath knight Sollicitour Generall to his majestie.

The humble peticion of the letherdressers inhabiting in the burrough of Southwark in the county of Surrie.

May it please your worshipp to be advertized that there being many of that trade, that have great charge of wife and children, and by reason of some abuses in the trade many having served seaven yeeres as apprentices have no worke, and so fall to decay and are impoverished occasioned by divers strangers Dutchmen who imploye their countrymen as joyrnymen to worke, having never served that tyme the law appointes, giving forth that they may doe it, and that it is and wilbe allowed of, that strangers may sett whom they please to worke at such trades as they use which cannot be but agreat greivance to the native English yf strangers should have more priveledg then they, besides ther be many prentices who now are bound for seaven yeares to divers of our trade take occasion thereby to seeke all meanes possible to goe from their masters and to be at liberty to work as joyrneymen as the strangers doe having not served above 3 or 4 yeares to their masters and our great hinderance. And we having peticioned for redresse herein to the justices of peace in the countye who toke great paines therein well knowing ours, and the state of the burrough of Southwarke as now it standes yet uppon some reasons and motives best knowen to themselves, have referred us and our suite to your worship for his majesties pleasure herein.

Wee therefore most humbly intreate your worship in regarde of our povertye not being able dailye to waite and attende as becommeth us that you would be pleased very speedily to sett downe a day for the hearing of this matter yourself, or els to referr it to Sir Edmund Bowyere and the rest of his majesties justices neare unto us in our county of Surry that by them it may not be long delayed and we as in duety bound will unfainedly pray for your perpetuall happines etc.

Report by David Moffatt

This was one of at least two petitions from the leatherdressers of Southwark in London complaining about Dutch encroachments on their trade that seem to date from January 1622. This one was submitted to Sir Robert Heath and the other to Sir Edmond Bowyer, Lieutenant of Surrey.[1]

Leather Dressers

The leather industry in the sixteenth and seventeenth century was second only to the woollen industry and rivalled the cloth industry. Leather skins were claimed to be more important than meat. However, the facts are that meat was about ten times that of leather by value. Leather was used not only for shoes and boots but all sorts of riding equipment and harnessing. The term dresser was applied to a worker in leather. In the seventeenth century there were about 3,000 shoemakers in London and about the same number of leather dressers and glovemakers. There were 80 tanneries in Bermondsey and Southward alone. Ten percent of the excise duty on leather came from London but the industry was more prolific outside London service bit local and international trade.[2]

In the seventeenth century the Dutch had a significant naval presence and they were one of the major carriers of goods for international trade, which gave then a deep knowledge of markets and opportunities for growth. Amsterdam was a major converter of raw materials into finished products. This generated skilled artisans whose reputation spread. This period was known as their Golden Age where they went from relative insignificance to a major influence in the world.[3]

The leather dressers of London particularly complained that the Dutch immigrants, who were competing with their trade and reportedly did not serve the same length of apprenticeships as local craftsmen, thus breaching the Statute of Artificers. By employing such journeymen, it seemingly created unemployment amongst locally trained people. There were many infractions of the rules but it was difficult for officers, who represented the trades bodies, to monitor these breaches.[4]

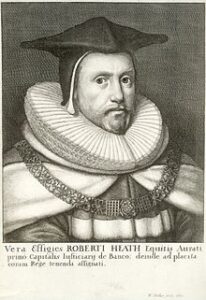

Sir Robert Heath (1575-1649)

Robert Heath, the recipient of this petition, was educated at Tunbridge Wells grammar school, St John’s College, Cambridge and Clifford’s Inn. He became a barrister of the Inner Temple in 1603. In 1621 he was elected Member of Parliament for the City of London and appointed solicitor-general in the same year, when he was knighted.

Robert Heath, the recipient of this petition, was educated at Tunbridge Wells grammar school, St John’s College, Cambridge and Clifford’s Inn. He became a barrister of the Inner Temple in 1603. In 1621 he was elected Member of Parliament for the City of London and appointed solicitor-general in the same year, when he was knighted.

In 1624 he was elected MP for East Grinstead. He served as Attorney General to Charles I from 1625. He owed his appointment to the favour of the Duke of Buckingham. Heath is credited with founding both North Carolina and South Carolina. He was on a commission to consider the tobacco trade with Virginia in 1627-8. Heath became Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas in 1631. However, he lost this position, due to his Calvinist stance in opposition to Archbishop William Laud. Heath returned to his practice as a barrister. His reputation as pro-Puritan, anti-Laudian did him no harm with the Long Parliament when Charles brought him back as a judge, making him Lord Chief Justice.[5]

References

[1] ‘James 1 – volume 127: January 1622’, in Calendar of State Papers Domestic: James I, 1619-23, ed. Mary Anne Everett Green (London, 1858), pp. 332-341. British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/jas1/1619-23/pp332-341.

[2] L.A. Clarkson, ‘The Leather Crafts in Tudor and Stuart England’, The Agricultural History Review, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1966), pp. 25-39, https://www.bahs.org.uk/AGHR/ARTICLES/14n1a2.pdf

[3] Donald J. Harreld, ‘The Dutch Economy in the Golden Age (16th – 17th Centuries)’, EH.net, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-dutch-economy-in-the-golden-age-16th-17th-centuries/

[4] Joseph P. Ward, Metropolitan Communities: Trade Guilds, Identity, and Change in Early Modern London (1997), p. 34.

[5] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Heath

This report is part of a series on ‘Petitioners in the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, 1600-1625’, created through a U3A Shared Learning Project on ‘Investigating the Lives of Seventeenth-Century Petitioners’.