Richard Crossing, late of Exeter, merchant. SP 16/513/2 f. 104 (1646)

To the honourable committee

The humble petition of Richard Crossing late of Exon merchant

Sheweth that your petitioner had 13 ballotts of canvas marked as in the margent; taken long since in the William of Topsham and carryed into Plimouth, which goods your petitioner (unto whom they belong) formerly conceived had bin taken by a private man of war, butt by late information findes they were taken by the Warwick frigatt and sold for the benefitt of the state, the sales wher of as per certificate under the commissioners hands amountes unto one hundred and eleaven pounds nineteene shillings and three pence

Your petitioner humbly prayeth this honourable committee to graunt him permission the to adde the sayd summe unto his former, that hath bin examined, in regard these goods were taken in the like manner, and neere the sayd time with them and your petitioner farther desires that himselfe with others who have ben greate sufferers, [illegible] well affected, and have long attended, may find releife att the last as to in that way as to your wisedome shall be thought fitt.

And your petitioner shall ever pray etc.

Report by Graham Camfield

The merchant Richard Crossing is seeking reimbursement for the cost of his canvas, taken by the Warwick frigate and sold for £111 ‘for the benefitt of the state’.

The Crossing Family

The Crossings were one of the leading merchant families in Exeter in the 16th and 17th centuries, playing a significant role in the administration of the city. Hugh Crossing (d. 1622) built up a prosperous business in cloth with a base in Marlaix, Brittany, and served as mayor of Exeter in 1609 and 1620. His son Francis (c.1598–1638) was MP for Mitchell (1626) and Camelford, in Cornwall (1628) and mayor in 1634.[1] Other family members, Thomas (1624 and 1637) and his son Richard (1654) also served as mayor.

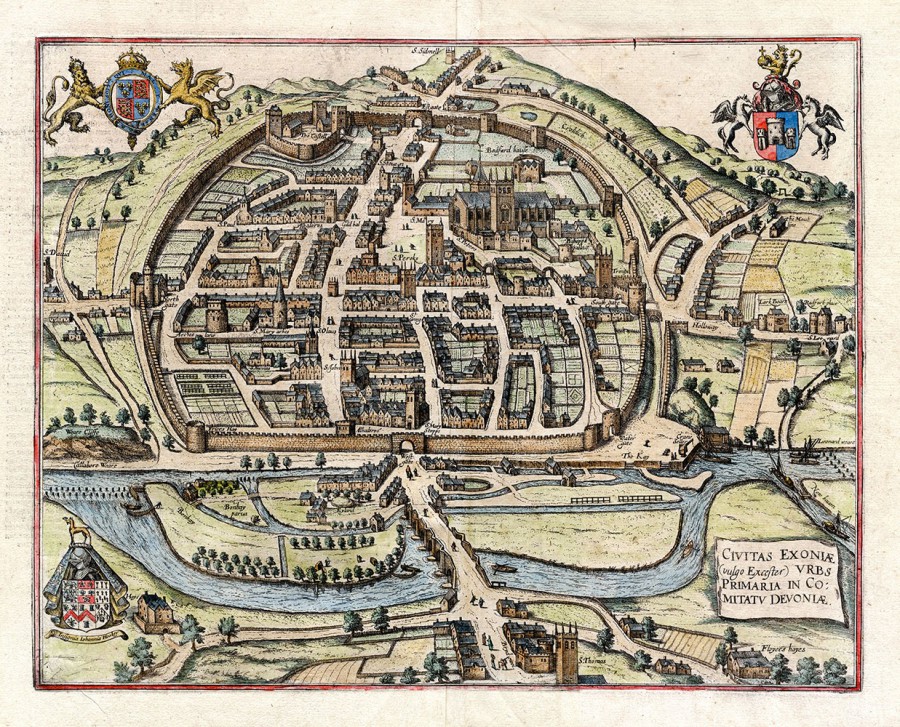

The Sieges of Exeter

The unsuccessful attempt by the Earl of Bath to raise support for the King in 1642 led the Puritan dominated Chamber to declare for Parliament and to strengthen the city defences. Between 1642 and 1644 the city endured two sieges with the Royalists finally taking control. During this period Richard Crossing was one of several prominent Exeter citizens chosen by Parliament to serve on committees charged with overseeing the gathering of sequestered funds and developing defence and the militia.[2] From 1645 conditions in Exeter and surrounding districts deteriorated as the New Model Army under Fairfax sought to retake the city. A further siege and the routing of Royalist forces led to the final surrender of the city to Parliament. On the 13 April 1646 Oliver Cromwell entered Exeter at the head of his New Model Army.

It was during the final stage of this conflict in 1646 that Richard Crossing petitioned for compensation for the loss of his cargo of canvas. Thirteen ballots [small bales] of canvas had been seized and sold “for the benefit of the State” i.e. Parliament, realizing almost £112 (around £12,000 today).[3] The port of Topsham was held by Royalist forces from 1642 to 1645, when it was taken by Fairfax. Canvas, of course, was valuable material, particularly for the manufacture of sails and tents.

It was not the first instance of such seizure and an earlier appeal for compensation by Richard Crossing and other merchants had still not been satisfied by 1652, some eight years later.[4]

Petition of John Willoughby, executor of Hen. Gough, Chas. James, Rich. Crossing, Sam. Coker, Fras. Lipping, Hen. Gould, and other merchants, to Parliament. In 1644 and 1645, their goods were taken at sea by Capt. Penn, and disposed of for the service, to their loss and undoing, and in 1646 the Committee for Petitions ordered Mr. Corbet to report to Parliament an ordinance for paying them 6,635l. 3s. 1d. [approximately £780,000], but the report has not yet been made, owing to other weighty affairs. Begs that it may be reduced to an Act, and they paid with interest out of moneys rising on sale of delinquents’ estates.[5]

Many of Exeter’s merchants had Puritan sympathies[6] and supported the cause of Parliament, but in spite of their allegiance many of them also suffered considerable financial loss at the hands of its officers. In July 1648 Richard Crossing was appointed to a “Commission for the Militia for the City and County of Exeter, for the better Securing and Safety of the Parliament and the said City and County”.[7] The following year he was elected Mayor of Exeter, but refused “because the Kingly government was then by armed violence obstructed”.[8] The execution of the King was a step too far.

The Crossings, it seems, were not extreme in their Puritanism but “were good churchmen according to the principles of the Reformation, loyal to the King”.[9] Some years later Richard Crossing appears to have come to terms with the Commonwealth, when, in 1654, he accepted the office of Mayor. It has been suggested that “either he swallowed his scruples later or could not afford to pay fines levied by the Commonwealth on those who refused to take office under the government”.[10]

Towards the end of his life he wrote an unpublished history of Exeter entitled A Catalogue or particular of the Antiquities &c. Special Remarkes of the Cittie and Chamber of the Cittie of Exon by Richard Crossing, sometime a member of the sayd Chamber, 1681.[11]

He died in 1682 and was buried, with a monument, in the parish church of St Mary Arches, long associated with Exeter’s mayors and merchants.

References

[1] ‘Crossing, Francis (c.1598-1638), of Exeter, Devon’, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629, ed. Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris, 2010, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/member/crossing-francis-1598-1638

[2] ‘April 1643: An Ordinance for bringing in the monyes for sequestrations out of the County of Devon.’, in Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660, ed. C H Firth and R S Rait (London, 1911), pp. 136-137. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/acts-ordinances-interregnum/pp136-137. July 1644: An Ordinance for the enabling the Committees herein named, to put in execution severall Ordinances of Parliament in the Counties of Wilts, Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, the Cities of Bristoll and Exeter, and the Town and County of Poole.’, in Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660, ed. C H Firth and R S Rait (London, 1911), pp. 459-461. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/acts-ordinances-interregnum/pp459-461

[3] ‘Charles I – volume 513: March 1646’, in Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles I, 1645-7, ed. William Douglas Hamilton (London, 1891), pp. 361-396. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/chas1/1645-7/pp361-396

[4] Petitions from merchants, &c. ‘House of Commons Journal Volume 3: 20 April 1644’, in Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 3, 1643-1644 (London, 1802), pp. 465-466. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/commons-jrnl/vol3/pp465-466.

[5] ‘Addenda’, in Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Interregnum, 1652-3, ed. Mary Anne Everett Green (London, 1878), pp. 620-622. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/interregnum/1652-3/pp620-622.

[6] ‘Exeter during the Civil War’, Exeter Memories website, http://www.exetermemories.co.uk/em/civilwar.php (accessed 25 November 2019).

[7] ‘House of Lords Journal Volume 10: 10 July 1648’, in Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 10, 1648-1649 (London, 1767-1830), pp. 372-374. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/lords-jrnl/vol10/pp372-374

[8] Alan Brockett, Nonconformity in Exeter, 1650-1875, Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 1962, p.7.

[9] W. Cotton and Henry Woollcombe, Gleanings from the Municipal and Cathedral records relative to the history of the City of Exeter (Exeter: 1877), p.74.

[10] Beatrix F. Cresswell, Exeter churches, Exeter: J.G. Commin, 1908, p.97.

[11] Historical Manuscripts Commission, ‘The city of Exeter: John Hooker’s books’, in Report on the Records of the City of Exeter (London, 1916), pp. 340-382. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/hist-mss-comm/vol73/pp340-382.

This report is part of a series on ‘Petitioners in the reign of Charles I and the Civil Wars’, created through a U3A Shared Learning Project on ‘Investigating the Lives of Seventeenth-Century Petitioners’.