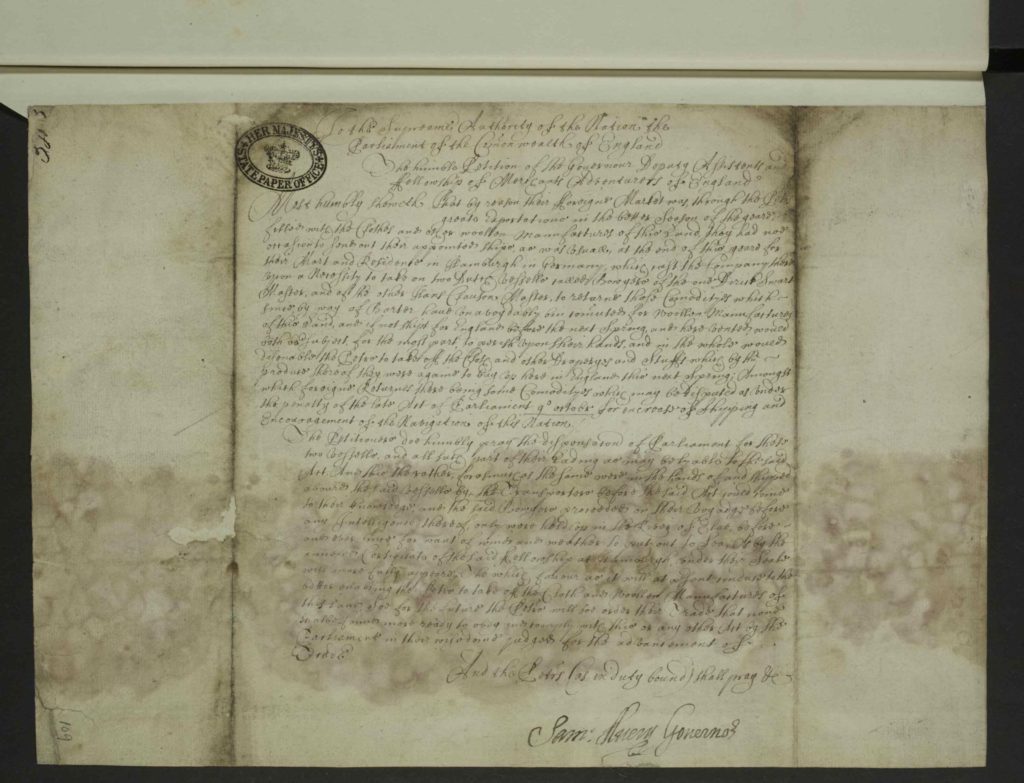

The monarchy was abolished in England from 1649 to 1660, but hundreds of people continued to submit petitions to the central authorities every year. While previously they had been addressed to the King or his Privy Council, petitioners in the 1650s mostly sent their requests to the new Council of State or later the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

As part of ‘The Power of Petitioning’ project, we have transcribed and published almost 400 of these manuscripts from across the seventeenth century on British History Online. We also completed a six-month Shared Learning Project with a large group of amateur researchers from the London Region of the University of the Third Age.

Each of these researchers wrote one or more reports about the petitioners and their requests or complaints. The introduction to this U3A project includes much more information, including important caveats about accuracy and interpretation. This set of 20 reports mostly cover the 1650s, beginning shortly after the execution of Charles I in 1649.

For example, in 1649 Richard Shakerly sought help from the Council of State because his ship had been seized at Falmouth four years before. As Sandra Linger shows, Shakerly had been seeking redress for years without little success despite having ‘allways testified a faithfull and cordiall affection to the Parliament’. A more dramatic petition came from the Merchant Adventurers who complained of ‘oppression and neglect’ in Hamburg in 1651, as investigated by Wendy Lewis. These merchants suggested the Parliament needed to do more to help them because they were being targetted by Royalists and their allies overseas. Even more sensational was the petition from Thomas Billingsley in 1652, which sought long-overdue compensation for the ‘horrible massacre’ of English merchants in Amboyna carried out by the Dutch East India Company thirty years earlier. As Janet Osbourne explains, Billingsley’s uncle was one of the Englishmen killed at the time, so the petition was an attempt to push the government to recompense the loss of his estate, according to their ‘sacred love to justice’.

These reports together show that people continued to seek favour or mercy from the central authorities through petitions, despite England’s abrupt shift from monarchy to republic.

The Petitions and the Reports

- 1649, Military officers and officers’ widows petition for arrears of pay before shipping to Ireland

- 1649, Richard Shakerly, mariner, asks for redress after his ship was seized at Falmouth

- 1650, George Wood, Commissary of Clothing for the Soldiers in Ireland, claims to be a victim of Sir John Clotworthy’s fraud

- 1651, the six gunners at the Tower of London petition Lord Bradshaw for their arrears of pay

- 1651, the Merchant Adventurers complain that they are mistreated and disparaged in Hamburg

- 1652, Thomas Billingsley seeks compensation for the murder of his uncle by the Dutch at Amboyna in the East Indies

- 1653, three Yarmouth ships’ masters request leave to depart from London during the Anglo-Dutch War

- 1653, Joseph Ames, shipmaster, requests leave to depart from London during the Anglo-Dutch War

- 1653, George Reade seeks a position as a ship’s clerk after financial losses and injury at sea

- 1654, Peter Dacton seeks the return of his ship, seized by a Commonwealth frigate

- 1655, the governor and officers of Dover Castle and the Cinque Ports ask Oliver Cromwell for their long-overdue salaries

- 1655, Lady Margaret Livingston and three other royalist widows petition Oliver Cromwell for their overdue pensions

- 1655, Thomas Marshall of Rye seeks reimbursement for supporting detained foreign seamen

- 1655, John Blackmore, army major, asks for his troops’ fuel and candle supplier to be paid so they can keep warm over the winter

- 1656, Henry Roach, John Wright, William Wood and partners seek to negotiate the terms of loan repayments to the Navy

- 1656, the heirs and executors of Sir Peter Rycaut request aid in obtaining letters of reprisal against the King of Spain

- 1657, Sir Thomas Vyner and Edward Backwell seek to mitigate financial losses from importing low grade silver bullion from Spain

- 1658, Henry Scobell, Clerk of the Parliament, seeks reimbursement for building repairs and his salary

- 1658, Mary Pitman hopes to receive her husband’s pay for his service as boatswain on the ship Tredagh

- 1659, Seth Ward, Professor of Astronomy at Oxford, asks that ‘an augmentation’ promised by Oliver Cromwell be paid

- 1660, John Cramp and other shipowners ask for help about a ship lost to the Spanish in 1642

For further petitions and reports from the rest of the seventeenth century, return to the main ‘Investigating Petitioners’ page.