We recently published The Power of Petitioning in Early Modern Britain, an open access collection of essays available to read for free from UCL Press. One of the contributors is Karin Bowie, Professor of Early Modern Social History at the University of Glasgow. We asked her about her chapter on ‘Gathering hands: political petitioning and participative subscription in post-Reformation Scotland’ and its place in her wider research.

* * *

How did you get interested in early modern petitioning?

For my PhD, I researched popular politics and the making of the 1707 Union in Scotland. I found a cache of petitions sent to the Scottish parliament in 1706 against the treaty of union. Amazingly, only one historian had looked at these closely, and only in an article-length study. Across the literature, they either were mentioned as evidence of national opposition to union or dismissed as the product of aristocratic machinations. I was fascinated to find over 20,000 signatures on dozens of petitions, ranging from urban magistrates and landowners to illiterate craftsmen and farm tenants whose names were recorded by church elders and notaries. Further research showed that the petitions were part of a strikingly modern attempt to influence the Scottish parliament with mass expressions of public opinion. These petitions launched 20 years of research on petitioning in early modern Scotland.

What is the most interesting petition or petitioner that you came across while researching this chapter?

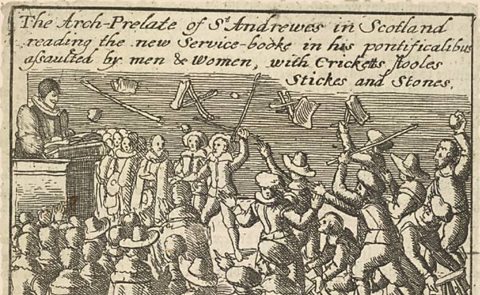

In the Scottish national archives, I found a letter written in 1637 by a noblewoman, Margaret Douglas, Lady Lorne, encouraging her husband’s kinsman to sign a petition against a controversial prayer book. Her heartfelt letter urged Sir Colin Campbell of Glenorchy to prove his Christian commitment, regardless of the dangers. This letter is significant for so many reasons: in relation to the history of petitioning, it shows female involvement in an early large-scale petitioning campaign; it reveals real concern for the dangers of petitioning and, conversely, the importance of religious beliefs in encouraging subscription. For Scottish history, it exposes hitherto unknown copycat petitioning activity in 1637 and reveals the involvement of Lady Lorne in this campaign before her husband Archibald Campbell, Lord Lorne (later the earl and marquis of Argyll) committed himself to the Covenanting cause. This single letter addresses so many dimensions of history by giving us a rare glimpse of female political activism.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading your chapter?

In talking to friends and colleagues about petitioning, I find that most of us have never thought about when or why petitions were first signed in large numbers. We don’t have a collective understanding of the origins of modern petitioning.

My chapter shows that signing a petition was not an obvious thing to do. Before the establishment of a modern right to petition, it could be dangerous to sign your name on a petition–the king could execute you for sedition. The idea of gathering the signatures of ordinary people would have been counter-intuitive: their opinions held little weight and many did not know how to write, so why would you bother? It took a special combination of circumstances to generate large-scale petitioning in Scotland. These included a hope that large numbers would provide safety, a desire to express religious convictions, a need to draw together a movement and a wish to hide local differences of opinion among elites by collecting lots of signatures from ordinary people. The surviving sources in Scotland provide a detailed case study that I hope will provide insights to researchers in other national contexts.

How does your work on this chapter fit into your current and future research?

This paper developed from a previous article that showed how a constitutional right to petition the monarch was created for Scotland through a revolution against James VII and II in 1688-89. It underlines the point that petitioning prior to 1689 operated under a customary liberty, not a right. Scottish monarchs tried to block large-scale petitioning when their opponents started to experiment with these methods in the late sixteenth century. This paper provides more detail on these contestations and considers why signatures were gathered despite the dangers.

Having explored Scottish petitioning up to the 1707 Union, my future research will explore petitioning after the Union. I’d like to understand how these early Scottish practices combined with English approaches in the new context of the Westminster parliament to produce British campaigns.