We recently published The Power of Petitioning in Early Modern Britain, an open access collection of essays available to read for free from UCL Press. One of the contributors is Brodie Waddell, Reader in Early Modern History at Birkbeck, University of London. We asked him about his chapter on ‘Shaping the state from below: the rise of local petitioning in early modern England’ and its place in his wider research.

How did you get interested in early modern petitioning?

It feels sometimes like I have always been interested in the history of petitioning. The idea of petitioning as a key tool for redress was a major theme in my PhD research which I completed about fifteen years ago, and I used a small sample of petitions to Yorkshire magistrates in one of the chapters of my first book. However, it was when I began talking to colleagues about it after starting at Birkbeck about ten years ago that petitioning became a real obsession. What I quickly learned is petitioning turned up everywhere in the early modern period, whether you were studying high politics and religious policy or neighbourhood relations and poor relief. That convinced me that some sort of collaborative project would be worthwhile, and this book – along with various other publications – has been the result.

What is the most interesting petition or petitioner that you came across while researching this chapter?

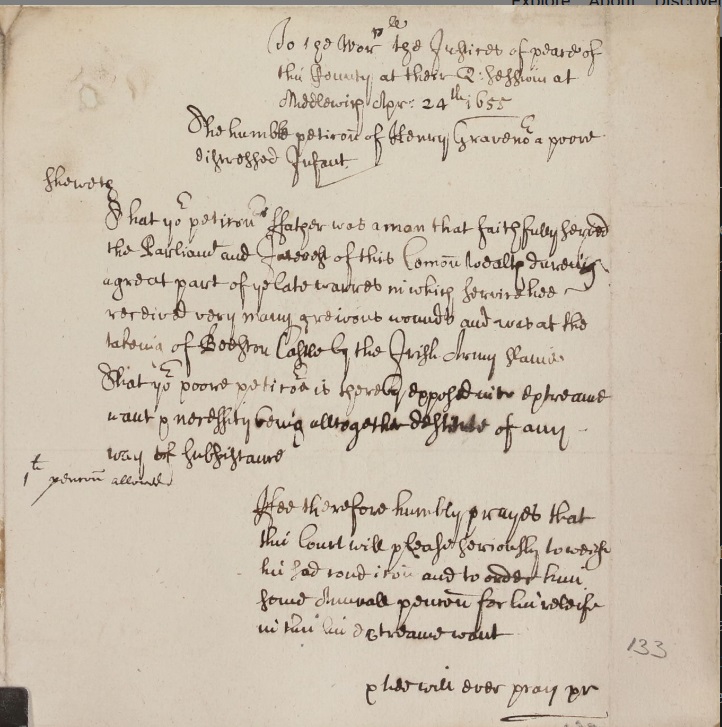

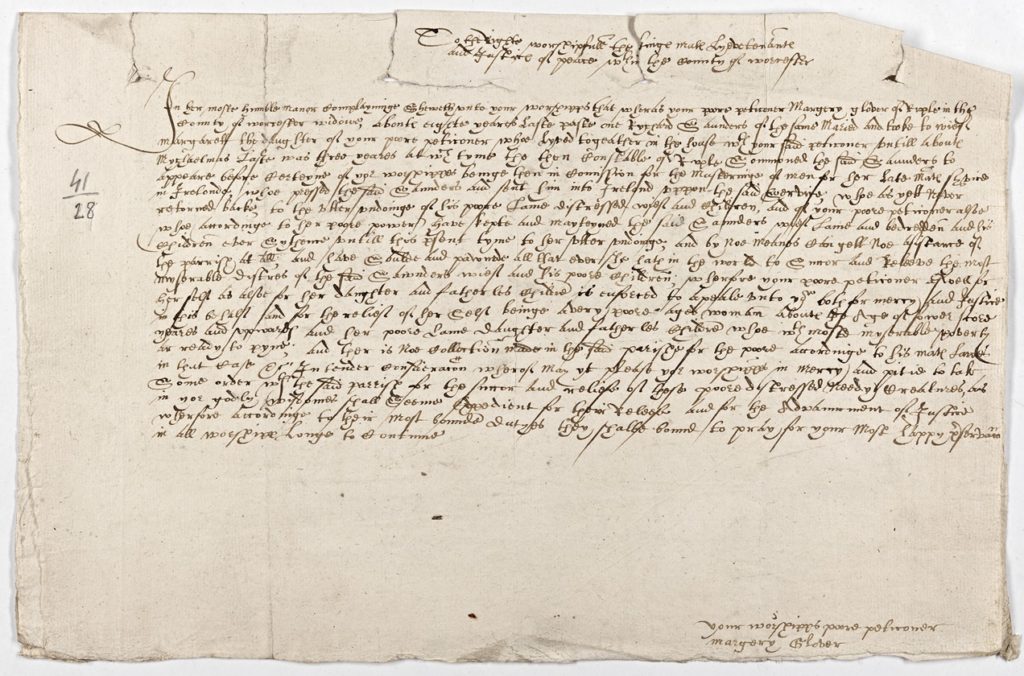

That prize has to go to Margery Glover, who submitted a petition for a poor relief order to the Worcestershire magistrates in 1605. There is nothing especially exceptional about her situation or her petition, but I think it wonderfully encapsulates the way local petitioning worked at the time. In the text, she appealed to very traditional ideas of paternalist mercy and protection, but also forcefully denounced the local parish officials for failing to fulfil their legal responsibilities to provide her with poor relief funded by local taxation. Her appeal was, according to the petition, ‘for their releefe and for the advauncment of justice’, that is to say it was as much about enforcing legal entitlements as about charitable pity. This widow’s complaint was successful and she was awarded four pence weekly, which is not only convenient in reinforcing my argument but also nice to discover when so much history of the early modern poor is profoundly grim.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading your chapter?

The main argument is very simple: local petitions were part of what might be called ‘state building from below’. They allowed many people without an official role in governance to put pressure on parish and county officeholders about issues that mattered to them, shaping the implementation of policies governing housing (cottage licences), sociability (alehouse licences), welfare (poor relief), taxation (parish rates), litigation (pardons), and much else. This was not entirely new, but there was a vast expansion in the practice of local petitioning in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in England, which suggests that we need to account for it in our narratives of state formation.

How does your work on this chapter fit into your current and future research?

In one sense, this collected volume was the culmination of several years of collaborative work on petitioning, and thus an ending of sorts. However, I’m afraid this isn’t the last you’ll hear from me about early modern petitioning. I am currently writing a monograph on the subject – almost fifty percent very roughly drafted! – and I have a recent article which looks more at the ‘political’ side of local petitioning.

I am also part of another collaborative project which, as I have discovered, has some overlaps with my work on petitioning. I’m currently working on Written Worlds: Non-Elite Writers in Seventeenth-Century England, and perhaps unsurprisingly, some petitioners were also involved in writing other sorts of texts and, conversely, some non-elite authors were involved in petitioning. So I’m now learning more about how petitioning fit into the wider culture of writing among people without an elite education or wealthy background.