[This post by Philip Carter, Director of Digital and Publishing at the Institute of Historical Research, was original published on the IHR’s ‘On History’ blog on 11 November 2020.]

This autumn the Institute of Historical Research’s British History Online completed a project to digitize and publish over 2,500 petitions from early modern England. The digitization project forms part of The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England, run by historians from Birkbeck and University College London.

The petitions, all now available free on BHO, offer remarkable insight into personal and community relations, preoccupations and language of grievance in early modern England. This makes for an excellent resource for research and teaching. In the final phase of the project, IHR Digital is now building a web interface to work with the BHO data, allowing this rich dataset to be explored in new ways.

Over recent months, editors at British History Online (BHO) have been hearing voices from early modern England. These are not the voices to which historians are most accustomed—those of the elite, literate or powerful whose views come down to us through official records and correspondence. Rather these are the voices of ordinary men and women who came together to raise concerns, submit requests or issue protests, and whose opinions were captured in thousands of signed petitions submitted to local officials, the crown and parliament.

BHO’s encounter with these voices comes from its involvement, as technical partner, in ‘The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England’. This is a two-year digitization and interpretation project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Council and Economic History Society, and led by early modern historians from Birkbeck and University College London: Brodie Waddell, Jason Peacey and Sharon Howard. For the IHR, the project’s been run by Jonathan Blaney, editor of BHO, and our senior developer, Kunika Kono. The original manuscripts were transcribed by Gavin Robinson and Tim Wales.

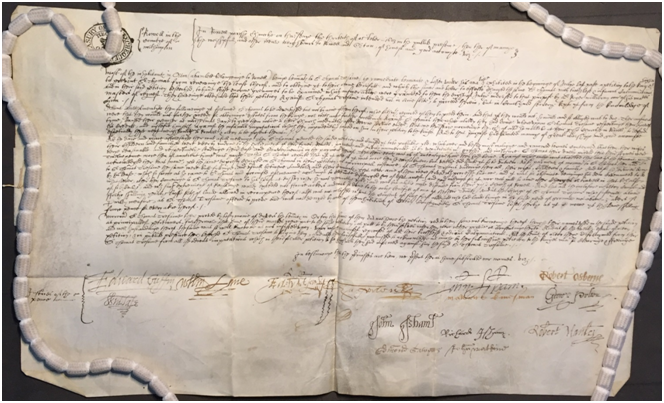

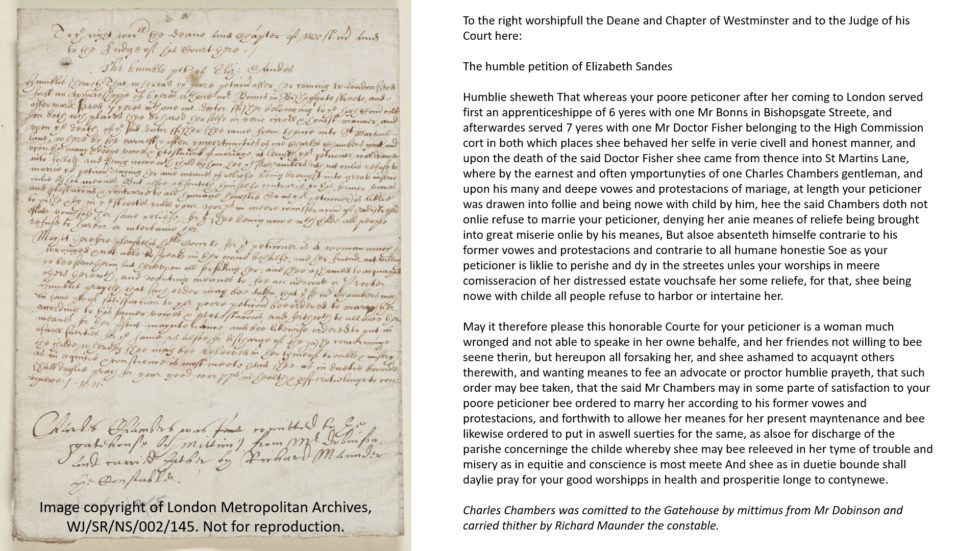

The ‘humble petition’ of Elizabeth Sandes (1620) in which she sought relief from the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey; shown here alongside the transcript published in British History Online. Unless granted, ‘your peticioner is liklie to perishe and dy in the streetes’

The ‘humble petition’ of Elizabeth Sandes (1620) in which she sought relief from the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey; shown here alongside the transcript published in British History Online. Unless granted, ‘your peticioner is liklie to perishe and dy in the streetes’In seventeenth-century England, petitioning was commonplace. It offered one of the few ways to seek redress, reprieve or to express personal and communal interests. Petitions were the means by which the ‘ruled’ spoke directly to those in power. As communications, they took many forms. Some were carefully crafted demands signed by thousands and sent to crown and parliament. Others were hastily written—and deeply personal—expressions of need or anger. Whatever their form, petitions reflect the seldom-heard concerns of supposedly ‘powerless’ people in early modern society. Continue reading “Letting the people speak: 2,526 early modern petitions on British History Online”